Conducting Rural Health Research, Needs Assessments, and Program Evaluations

Rural communities and healthcare facilities may have limited resources to address many health-related needs. Research and needs assessments can help determine where and how resources may best be focused, and program evaluations can indicate whether a particular intervention or approach works well in a rural context, while also leading to evidence of a promising or best practice.

Individuals and teams who understand the purposes of conducting research, needs assessments, and program evaluations, and who have the tools to undertake such activities, will be better positioned to focus their efforts where they will have the best result. Likewise, policymakers, leaders, funders, and other decision-makers who understand how to help rural communities by supporting rural health research, assessments, and evaluations can help build our nation's understanding of rural health needs and effective interventions to address those needs.

Given the importance of research, assessment, and evaluation to rural interventions and policy, the best rural health research and community assessments include a member of the community as a member of the research team helping to ensure that the community’s confidentiality concerns are addressed, programs are appropriate, and language is accurate and reflects the culture of the community.

This guide:

- Identifies the similarities and differences among rural health research, assessment, and evaluation

- Discusses common data collection methods

- Provides contacts within the field of rural health research

- Addresses the importance of community-based participatory research to rural and tribal communities

- Looks at the community health needs assessment (CHNA) requirements for nonprofit hospitals and public health

- Examines the importance of building the evidence base so interventions conducted in rural areas have the maximum possible impact

Frequently Asked Questions

- What are the purposes and roles filled by research, needs assessment, and program evaluation in the rural health arena?

- What are common data collection methods used in research, assessment, and evaluation?

- What are special considerations for keeping collected data private and secure?

- When should we conduct a needs assessment and plan the program evaluation for our rural community health project?

- What kinds of questions does rural health research seek to address?

- Who conducts rural health research?

- What funding is available to support rural health research?

- How do you select an appropriate rural definition for a research study?

- Are there concerns unique to rural areas researchers should keep in mind?

- What is community-based participatory research (CBPR) and how can it help rural communities and researchers work effectively together?

- What is tribally-driven participatory research (TDPR), and how is it different from CBPR?

- What is comparative effectiveness research (CER) and how can it help us understand how well specific healthcare interventions work for rural residents?

- What is the role of practice-based research networks (PBRNs) and what are some examples of rural PBRNs?

- How and where can you share rural health research results?

- What are some different types of assessments relevant to rural health?

- What are the main steps in planning for and conducting an assessment?

- What are the requirements for nonprofit hospitals to conduct Community Health Needs Assessments (CHNAs)?

- What are the community needs assessment requirements for public health agencies related to the Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB) accreditation standards?

- How can rural hospitals and public health agencies work together to conduct community assessments?

- What CHNA tools and resources are available for rural facilities?

- What are the different purposes that evaluation can serve?

- Why is it important to evaluate rural health programs?

- How can rural programs plan for and conduct efficient and practical program evaluations?

- What tools are available to help rural grantees learn about program evaluation?

- How can funders ensure their grantees' experiences help build the collective understanding of what is effective in addressing rural health issues?

What are the purposes and roles filled by research, needs assessment, and program evaluation in the rural health arena?

Rural health research, assessment, and evaluation are all processes that seek to improve the health and well-being of rural populations through better understanding. These three activities often overlap, share similar methods, and may be defined differently depending on who you ask.

For the purpose of this guide, we will discuss them as follows:

Research seeks to discover new knowledge or test ways of knowing through investigation. Researchers seek to answer specific research questions, meet their stated research aims or objectives, or test a theory or hypothesis.

Needs assessments seek to measure, or assess, the circumstances present in a specific community, organization, or program. Assessment can be used to identify needs or gaps in available rural health services, as well as assets and strengths.

Program evaluation focuses on determining how well a program, service, or policy is doing in terms of meeting specific goals and objectives. Ideally, the goals and objectives were identified prior to implementation of the program, or at minimum, prior to knowing the program's impact. The focus of program evaluation is to improve how a program, service, or policy is delivered; identify how to sustain impact of program activity; and produce data to inform decisions. The subject of the evaluation is decided based on the values of people or organizations who are served by the program, implementing the program, funding the program, or might otherwise use the evaluation findings.

All three activities can be conducted by a community, healthcare facility, government agency, academic institution, or others, assuming the investigators have the appropriate skills or a mentor to help develop those skills.

Before you begin an inquiry, determine whether you intend to perform research, assessment, or evaluation. Clarifying your purpose will help you select the appropriate methods and team members for conducting your work and later documenting and sharing what you learn.

| Characteristic | Research | Needs Assessments | Program Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intended to answer a question or set of questions | Yes | Yes, a desire to understand the state of affairs | Yes, is the implementation going according to plan and is the program or policy having its intended effect? |

| Involves an intervention | May or may not | No | May or may not. Program evaluations can be done with programs that are not implementing interventions. |

| Has measures defined in advance | Yes, could also identify objectives or aims | May or may not | Yes |

| Includes baseline data | May or may not | Can serve as baseline data or can be compared to previous assessments | Ideally, yes. However, it may be possible without baseline data, depending on how the goals and objectives are defined and on the program timeline. |

| May be funded by a grant | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Findings may be published in a journal article | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Helps build the knowledge base of rural health | Yes | Yes | Yes |

What are common data collection methods used in research, assessment, and evaluation?

Many methods are available to gather evidence. Selecting the appropriate methods will depend on the questions you have in mind, the resources and expertise available, and time and geographic constraints. While this is not an exhaustive list, it covers some of the more common tools.

Surveys use sets of questions, which can be asked in-person, by phone, on a paper form, or online. These questions can be directed to an individual, such as a rural resident or healthcare professional, or to an institution, such as a rural hospital. A survey, or questionnaire, might be used by itself for point-in-time information, or before and after an intervention to see if there is a change in circumstance. There is a science to developing surveys. Consider using existing tested and validated survey instruments or working with someone who has expertise in survey design. Learn more about survey design from the American Association for Public Opinion Research’s Best Practices for Survey Research.

Interviews are discussions between an interviewer and another person, who may represent themselves individually or represent an institution. Interviews are less structured than surveys but usually include a list of questions developed in advance. A key informant interview, for example, is used to find out in-depth information about a community or organization by asking a community member for their insights. Like surveys, interviews can be done in person, over the phone, or online through a video conferencing system. It can also be helpful to record the interview. Recorded interviews should always be done with permission of the participant and make clear the plan for analysis of the interview data.

Focus groups are group interviews. A facilitator leads a gathering of participants, all of whom share some common characteristic, such as living in the same rural community or belonging to a similar interested group. Like the interview, a focus group is less structured than a survey, but it is based on pre-determined questions to guide the discussion. Because of interactions among the participants, it may offer rich insights that would not be obtained individually.

Observation involves the investigator watching participants do something that is of interest. For example, a study might observe how healthcare workers interact with a telemedicine program in providing care to patients. Observation is also common in program evaluation. For example, a rural public health provider might put up new signage about designated smoking spaces and observe the space to see if the signage works.

Abstraction is the process of extracting data from records and putting it in a usable format to be studied. For example, a study could involve pulling specific information from a set of medical records to determine if best practices were followed.

Secondary data can be taken from existing data sources and is typically already in a usable format. For example, a needs assessment might draw on data collected by various state and federal sources. For more information on data sources, see Finding Statistics and Data Related to Rural Health.

Artifact review is the process of looking at and analyzing artifacts. Artifacts are tangible items that a team can examine and assess in research, evaluation, and needs assessments. Artifacts can include pictures, printed advertisements, maps, primary sources, existing policies, or signage, for example.

What are special considerations for keeping collected data private and secure?

Whether you are collecting data for research, assessment, or evaluation, it is your obligation to make sure that it is managed in a responsible manner, particularly any information that relates to an individual or family. You should communicate how you intend to maintain the privacy of participants in the cover letter, information sheet, or focus group agreement.

In rural areas, where people may know more about one another and where various characteristics can make it easier to pick out a person from the crowd, it is even more important to consider how data is handled and stored. The National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics Toolkit for Communities Using Health Data includes information on de-identification, data security, and other topics for protecting data.

Funders, and federal funders in particular, have specific requirements and processes to protect the well-being and safety of participants. For example, studies that receive funding through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and that involve human subjects are subject to review by an institutional review board (IRB), which is regulated through the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP). The purpose of an IRB is to protect the rights, well-being, and welfare of research participants. It is recommended that, whenever it is possible and feasible, individuals involved in research, evaluation, and assessment secure IRB approval.

It is important for researchers and evaluators to be aware and considerate of the community context in which they will be working. For instance, local cultural norms will differ from place to place and population to population. Historical experiences of a population may also have resulted in mistrust of researchers and medical professionals.

Data collection that is occurring in a rural area that happens to include tribal communities/reservations must also consider tribal sovereignty. When working with or on reservations, researchers and evaluators must recognize tribal jurisdiction, showing respect and obeying the laws and tribal government of that community. Some tribal communities will have their own research guidelines and IRB approval processes. Researchers and evaluators must speak directly to tribal leadership to secure permission before engaging in research, evaluation, or assessment.

For more on the relationship between researchers and communities, see the FAQs What is community-based participatory research (CBPR) and how can it help rural communities and researchers work effectively together? and What is tribally-driven participatory research (TDPR), and how is it different from CBPR?

When should we conduct a needs assessment and plan the program evaluation for our rural community health project?

Needs assessments and program evaluation planning should be included at the start of a rural project:

- Conduct a needs assessment to identify the issues to address and identify helpful resources

- Select and adapt, as necessary, a program with goals aligned to meet the identified need and that is feasible given the available resources

- Plan how you will evaluate the program and identify baseline data, if they exist

- Begin implementation

It can be appealing when you hear about a successful project in another rural community, or a set of activities that sound useful, to decide that it is the right intervention to use. However, there is no guarantee the circumstances in the other community are similar enough to your own for the same intervention to work.

A needs assessment conducted prior to the beginning of program planning and implementation will be most effective. Understanding the current circumstances, needs, and strengths can help program planners select and adapt an intervention that is a good match for their community. Learn more about rural health needs assessments in the second section of this guide.

Rural communities, in particular, face challenges if they invest resources in a poorly focused intervention, such as:

- Not addressing the intended goals of the program

- Not being able to afford an alternative intervention if the first is not successful

- Losing the confidence of community members, which may be difficult to renew for future projects

- Losing the confidence of the project's funder, especially in an area where there are likely limited sources of funding

A program evaluation should be designed in the planning stage of a project. This will clarify the rationale for the program and how the proposed activities target the needs the program intends to address. Planning the evaluation before you begin will ensure you are measuring needs and circumstances within the direct and immediate control of the program. You can learn more about rural program evaluation in a later section of this guide.

Consider conducting an evaluability assessment to inform planning the evaluation. An evaluability assessment is a tool to examine the readiness of a program for evaluation, meaning assessing whether program conditions exist to produce useful data to inform decisions. The program may be in pre- or early intervention phase, and it may be too early to perform an evaluation to examine the program impact. Impact evaluations can be costly so assessing the readiness for evaluation can help in assessing the methods and type of evaluation needed. Learn more about evaluability assessments in Evaluability Assessment to Improve Public Health Policies, Programs, and Practices.

Rural Health Research

What kinds of questions does rural health research seek to address?

Rural health research is an umbrella term describing questions about rural healthcare services, the rural public health infrastructure, and how they intersect to improve the lives of rural populations. Research about rural healthcare services focus on a wide range of topics such as the delivery of rural healthcare services, the viability of rural healthcare facilities, and the rural healthcare workforce. It is part of the field of health services research that looks more broadly at healthcare access, quality, and cost. Rural public health research develops the evidence base needed to make informed decisions about interventions and policies to improve long-term health of rural communities through health promotion and disease prevention efforts through partnerships in various community settings. Rural public health research also examines variables that impact population health, personal health, and health behavior in rural areas, including social determinants of health.

Rural health research can also examine outcomes for rural populations. For more information, see What is comparative effectiveness research (CER) and how can it help us understand how well specific healthcare interventions work for rural residents?

Some examples of questions rural health researchers study include:

- How do health workforce supply and demand compare in rural versus non-rural locations?

- How does access to health services vary by population groups within rural areas?

- What policy-relevant insights can we discover by examining what is going well for certain segments of a rural population?

- What is the availability of a specific health service, such as obstetrics, in a rural area?

- What is the impact of a rural Medicare reimbursement change (proposed or implemented) on the financial stability of rural hospitals?

- How does the health status of rural residents compare to non-rural residents?

- What are the health behaviors of rural residents, such as tobacco use and physical activity?

- How do environmental, structural, or socioeconomic factors impact the health of rural populations?

Rural health research or studies may be driven by many things, such as:

- A research agenda for a specific topic developed by a group with an interest in the field and in collaboration with rural community members

- Requests for proposals from federal and state government, foundations, payers, or others with an interest in the efficiency and quality of the healthcare system

- Practical problems a healthcare provider is trying to solve, such as how to best implement a service

- The existing literature, which may identify gaps in knowledge or inspire additional questions

- The researcher's professional interests

For more on how research questions are developed see the 2019 article Formulation of Research Question – Stepwise Approach or Problem Formulation in William Trochim's The Research Methods Knowledge Base.

Some funding agencies will ask you to develop a research aim instead of a research question or hypothesis. The National Institute of Health (NIH), for example, requires all research projects to not only list research aims but also include a research aim(s) page in all applications. To learn more about research aims, see Writing Specific Aims from NIH.

For a broad overview of the health services research process, see Research Fundamentals: Preparing You to Successfully Contribute to Research from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI).

Who conducts rural health research?

The Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP) funds rural health research centers to study issues of current, national concern related to rural health. The Rural Health Research Gateway lists current FORHP-funded centers, as well as the research projects and findings underway and completed. It also lists a number of previously funded rural health research centers and their work.

Health services researchers at other organizations also study rural health issues. Some of these researchers work at academic centers focused specifically on rural health. Others may be part of an academic department, research organization, or other group that has another primary focus, such as nutrition, healthcare administration, or healthcare workforce, and includes "rural" as an aspect of their research because it relates to their primary field. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention established the Office of Rural Health and has made the development of rural public health one of its major strategic visions. Other federal agencies that engage in rural health research include the Department of Veteran Affairs Office of Rural Health, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

For a selected list of centers that conduct or otherwise support rural health research, please see the Organizations section of this guide.

What funding is available to support rural health research?

In addition to funding provided by the Health Resources and Services Administration through the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy and its Rural Health Research Centers program, these federal agencies also support research on rural health topics:

- The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) offers a number of funding programs that support health services research, which includes an interest in rural healthcare delivery

- National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) supports health disparities research, including interest in rural populations

- The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) funds rural economic, infrastructure, and agricultural research projects through its Agriculture and Food Research Initiative

- The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs funds VA employees to conduct investigator-initiated research that includes a priority area for healthcare access and rural health through its Health Services Research & Development Service

Other national organizations also support rural health research:

- The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) is a nonprofit, non-governmental organization that supports patient-centered comparative clinical effectiveness research and focuses on residents of rural areas as a population of interest

- Tribal Epidemiology Centers offer support, services, and funding to improve public health capacity and data availability for tribal communities

Grants.gov also manages a long list of funding that is currently open, posted, or scheduled. You can search funding opportunities by entering "rural" as your keyword.

Some philanthropic organizations have an interest in rural health that may include funding rural health research. For example, the Hearst Foundation and the Helmsley Charitable Trust have supported research related to their funding interests.

To browse specific funding opportunities for rural health research, see the Funding section of this guide.

How do you select an appropriate rural definition for a research study?

A 2005 American Journal of Public Health article, Rural Definitions for Health Policy and Research, discusses the importance of using an appropriate rural definition to develop research findings that offer accurate conclusions. The three key considerations the authors identify for selecting a rural definition to use in a research project are:

- The purpose of the study

- Availability of data

- Appropriateness and availability of the definition

The authors recommend researchers learn about the various definitions and the pros and cons of each early in their research process. The paper points out not only the differences between urban and rural areas, but also across rural areas, depending on their population size, geographic isolation, and other factors. Any definition will either under- or over-represent rural or urban in some way. Definitions that use only two categories, rural and urban, with no gradations within the rural category, may miss local issues that impact particular types of rural communities.

In What is Rural?, the USDA Economic Research Service (USDA ERS) describes the various definitions of rural and urban, noting that "rural and urban are multidimensional concepts" that can be defined by population density, geographic isolation, population size — each of which can define certain areas as rural or not rural depending on the metric. The end of the article offers links to data sources from the Office of Management and Budget and the U.S. Census Bureau. The USDA ERS also maintains Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes, which classify census tracts on a scale of 1-10 based on census data including population density, daily commuting, and urbanization.

The 2022 article Measuring Rurality in Health Services Research: A Scoping Review notes that varied and inconsistent use of the various rural definitions in research can have impacts on rural health policy and funding. Considerations for Defining Rural Places in Health Policies and Programs, a 2020 report from the Rural Policy Research Institute Health Panel, also outlines concerns about different rural definitions and challenges related to data collection. In the conclusion to the report, the authors list options for defining rural places, including basing definitions on the goals and purposes of a policy or program and adding criteria to identify a specific geography.

For more details about current rural definitions, see our What is Rural? Topic Guide.

Are there concerns unique to rural areas researchers should keep in mind?

Aside from concerns about how to select an appropriate rural definition, additional issues rural health researchers should consider include:

- Rural populations pose statistical challenges due to their small population sizes. These challenges include unreliable estimates, limited generalizability, and high data suppression to protect personal identifiable information.

- Issues related to smaller populations may also affect research on sub-populations in rural areas, so care must be exercised when combining demographic or other data.

- Researchers and Institutional Review Boards need to ensure data is reported in a manner that protects individual and community identity. Sometimes, results will not be able to be reported for small geographic units because participants are potentially identifiable. See What are special considerations for keeping collected data private and secure?

- The potential need for an onsite healthcare facility collaborator to recruit participants that meet the study requirements.

- Researchers seeking to collaborate with rural facilities should be aware that there may be resource limitations at these facilities and be sensitive to any time or other burdens the project may cause.

- When studying only one or a few rural communities, it may not be appropriate to generalize findings to other regions or other types of rural communities. The variety of rural communities, from Appalachia to Alaska, from island communities to mountainous areas, and from tourist-based economies with population fluctuations to areas with a steadier population, can impact many aspects of healthcare.

- Travel time and cost incurred by researchers for studies that require them to be present in-person either in the community or at a research data center.

- Cultural differences for both rural and tribal communities that may impact the most effective methods for engaging with study participants.

- Skepticism or distrust of academic organizations, concerns about privacy, or concerns about the implication of the research on policy or funding issues affecting their communities.

A 2018 findings brief from the North Carolina Rural Health Research Program, Range Matters: Rural Averages Can Conceal Important Information, discusses the importance of looking at highs and lows in data rather than just relying on averages. It argues that rural health data may include more extreme values than urban data and provides three rural examples illustrating the benefit of considering the range as well as average.

A 2018 National Center for Health Statistics report, U.S. Small-area Life Expectancy Estimates Project: Methodology and Results Summary, discusses both the challenges of and importance of looking at mortality outcomes for small geographic areas such as census tracts. It describes a methodology developed to calculate reliable life expectancy estimates for census tracts with small populations.

The 2013 Journal of Rural Health article, Community Outreach and Engagement to Prepare for Household Recruitment of National Children's Study Participants in a Rural Setting, offers the following recommendations for undertaking a rural research project:

- Build relationships with rural organizations and healthcare facilities for 1-2 years prior to study in order to establish trust

- Connect with Cooperative Extension agents to learn about the community

- Help build research capacity at rural healthcare facilities, as they may have limited research experience and infrastructure

- Engage with community members at parades, county fairs, and local events

- Stay involved by being present at community events as the study continues

Researchers can also partner with the community in sharing findings, as a way of demonstrating the research effort is mutually beneficial.

Additional sources that discuss special concerns rural health researchers should consider:

- A Review of Common Limitations in Rural-Related Studies in the Peer-Reviewed Literature, ETSU/NORC Rural Health Research Center, 2025

- Challenges of Using Nationally Representative, Population-Based Surveys to Assess Rural Cancer Disparities, Preventive Medicine, 2019

What is community-based participatory research (CBPR) and how can it help rural communities and researchers work effectively together?

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) defines community-based participatory research (CBPR) as

“an approach to health and environmental research meant to increase the value of studies for both researchers and the communities participating in a study.”

When using the CBPR approach, community members, healthcare facilities, and other interested parties work alongside researchers. This cooperation should begin as early as setting a research agenda and identifying community needs and continue through dissemination of research findings, implementation of interventions, and on to future studies. The development of an ongoing relationship between the community and the researchers is an important piece of CBPR. It helps develop trust and participation and ensures the work undertaken is relevant to the community and that findings and interventions benefit the community, not just the researcher's academic interests. CBPR may serve as an opportunity to build local research and evaluation capacity.

Researchers coming to a rural community can be perceived as outsiders, so developing an advisory board and building a presence in the community early on in the research process is important. The 2022 article Codesigning a Community-Based Participatory Research Project to Assess Tribal Perspectives on Privacy and Health Data Sharing: A Report from the Strong Heart Study describes implementing a CBPR approach in the early stages of a three-phase project to develop a tribal data sharing framework. The involvement of community members may vary throughout the process due to their interests and ability to contribute to different stages of the work. Researchers may also face challenges to community engagement, depending on their research topic. It is helpful to use a CBPR approach that can adapt to the needs of a particular community partnership. For more information on how CBPR is implemented in rural communities, see the 2019 article Establishing a Community-Based Participatory Research Partnership in a Rural Community in the Midwest and the 2008 article Evaluating a Community-Based Participatory Research Project for Elderly Mental Healthcare in Rural America.

What is tribally-driven participatory research (TDPR), and how is it different from CBPR?

Indigenous communities have an interest in CBPR, and in particular tribally-driven participatory research (TDPR), to ensure research conducted will contribute to the health of Indigenous communities and be respectful and appropriate to a community's culture, with power distributed equally between the tribal government and the researcher. TDPR differs from CBPR in that researchers must work with tribal governments, potentially use tribal research codes, and navigate data ownership and intellectual property. Project funding allocation should account for the costs of oversight and planning. The personnel budget should include salaries/wages for tribal community members which helps build tribal research capacity, improves the accuracy of research results, and compensates them for their knowledge and labor.

TDPR, as outlined in the 2009 article Tribally-Driven Participatory Research: State of the Practice and Potential Strategies for the Future, involves:

- Informed consent, usually through a written form, from the tribal council. This may also involve a formal contract or institutional review board (IRB) permission.

- Full participation in the research design process at the earliest opportunity and agreement on the goals, design, and implementation of the project.

- Care when gathering data. Utilizing tribal members for accurate translation can help ensure valid results. A plan should be made to protect the privacy of participants who may feel uncomfortable sharing sensitive information with fellow community members.

- Building on community strengths, building research capacity, and creating short and long-term benefits.

Given the long history of researchers coming into tribal communities and conducting research that did not benefit participants, tribal communities may find TDPR useful to prevent this type of encounter and help shape research that meets their community's needs. The Strong Heart Study and Strong Heart Family Study is a longitudinal study investigating cardiovascular disease in American Indian communities. Two 2025 articles, 35 Years of Partnership to Advance Cardiovascular Health and Well-Being in American Indian Communities: The Strong Heart Study and Strong Heart Family Study and Initiating Research in Indian Country: Lessons From the Strong Heart Study describe the successful partnership between researchers and tribal communities. Research projects that prioritize tribal participation and collaboration should:

- Understand and respect local culture including tribal government, data sovereignty, and cultural practices

- Build trust through regular communication about the study’s goals, potential risks, and expected benefits for the community

- Align study goals with community priorities

- Contribute to building local research capacity

- Conduct the study transparently by hiring from within the community where possible

- Share study results and accept feedback from the community

What is comparative effectiveness research (CER) and how can it help us understand how well specific healthcare interventions work for rural residents?

Comparative effectiveness research (CER) helps inform healthcare decision-making by comparing different treatment options. It looks at how well a particular procedure, medication, test, or other healthcare intervention works compared to other options. CER may focus on how well a treatment works for a particular group based on a particular demographic variable. When focused on rural health, CER examines healthcare outcomes for a particular treatment or intervention used in a rural setting.

By gathering evidence about the effectiveness of different treatments for rural populations, CER can help support:

- Rural clinicians and healthcare facilities deciding on what interventions to use

- Rural patients and their families selecting among treatment options

- Health insurance companies and other payers deciding what preventive care and treatments to reimburse and at what level

- Policymakers evaluating effective approaches in a rural setting

The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), which was established in 2010, seeks to help patients, families, caregivers, and the broader health and healthcare community make informed healthcare decisions through funding patient-centered comparative clinical effectiveness research. PCORI funds studies that address populations of interest, including residents of rural areas, and summarizes findings from those studies.

Public and patient engagement is central to the patient-centered CER studies PCORI funds, an approach that is influencing others in health services research. PCORI provides a range of resources to help researchers and their community partners better understand what the Institute seeks in applications. This partnership is key in ensuring that potential PCORI-funded studies reflect real world decisions faced by patients and those who care for them. These resources may be useful for and applicable to all types of research noted above and not limited solely to the patient-centered CER PCORI funds. PCORI’s Foundational Expectations for Partnerships in Research, a resource co-created with patient and stakeholder input, identifies and describes the building blocks necessary for meaningful, effective, sustainable engagement of communities, including rural communities.

To help communities and researchers better prepare to participate in and disseminate CER findings, the Eugene Washington PCORI Engagement Award Program funds projects to increase communities' knowledge and understanding of CER, as well as their ability to disseminate PCORI-funded evidence. PCORI participated in a June 2019 briefing on Capitol Hill to raise awareness of rural health research. PCORI’s website describes funded rural projects and includes a searchable list of all PCORI awards.

PCORI issues research funding announcements throughout the year, from its regular "broad" funding announcements, typically calling for investigator-initiated topics, to larger, targeted funding announcements with greater specificity regarding what the Institute is interested in addressing. PCORI provides resources on CER methodology and its application review program to guide potential applicants. Additionally, PCORI issues funding announcements for Dissemination & Implementation Funding Initiatives that help turn evidence from PCORI-funded studies into real-world practice.

What is the role of practice-based research networks (PBRNs) and what are some examples of rural PBRNs?

Practice-Based Research Networks (PBRNs) are networks of healthcare providers who seek to improve community health by translating research findings into clinical practice. Often PBRNs also include academic researchers as part of the network. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) provides an overview of primary care PBRNs.

Because a PBRN's research agenda is shaped by practicing clinicians, it can focus on issues with practical relevance for patient care. As discussed in the 2014 Journal of Rural Health article Recruiting Rural Participants for a Telehealth Intervention on Diabetes Self-Management, academic researchers can develop stronger connections to rural communities and potential research participants by working with local healthcare providers via PBRNs. Involvement in a PBRN can also help rural clinicians build their local research capacity.

Some of the roles of PBRNs, according to AHRQ, include:

- Conducting comparative effectiveness research

- Supporting quality improvement within the member primary care practices

- Developing an evidence-based culture

AHRQ maintains a list of PBRNs including several rural PBRNs, such as:

- The High Plains Research Network, which serves eastern rural Colorado and undertakes research studies and quality improvement projects on many topics.

- The Oregon Rural Practice-based Research Network (ORPRN), a group of primary care practices and community organizations in Oregon focused on improving the health of rural residents. ORPRN conducts studies on a range of health topics and primary care delivery issues.

- The Rural Oklahoma Network (ROK-Net), a state-based rural PBRN, focuses on recurring problems in rural primary care.

- The Texas A&M Health Science Center Rural and Community Health Institute, another state-based rural PBRN.

- The Rural Research Alliance of Community Pharmacies, a multi-state PBRN serving rural community pharmacies.

How and where can you share rural health research results?

Rural health research results can be shared in many ways. Two key factors to consider are:

- Where does the audience for the intended results typically seek information?

- How quickly do you hope to get your results out?

The same project may be shared more than once in order to take advantage of the benefits of different formats as the research project unfolds:

| Format | Best For | Keep in Mind |

|---|---|---|

| Reports to the funder and/or community organizations | Information that may need to be kept private Projects with no time constraints |

Not likely to reach a broader audience. Does not build the evidence base. |

| White papers, policy briefs, infographics, and other documents published directly by an organization | Practical information and lessons learned Reaching practitioners and decision makers quickly with useful information |

Web-based distribution typically has the broadest reach. Print copies may

be useful for special audiences and events. |

| Media releases and interviews, including podcasts and/or radio | Reaching a large audience, particularly the general public | Be sure that media outlets pursued can help you reach your target

audience. When working with the media, you give up control of how your results are portrayed. |

| Social media | Reaching a broad audience | Works best to promote a product, such as a white paper or media article |

| Conference presentations and posters | Practical information and lessons learned Reaching practitioners quickly with useful information Sharing early stages of research process |

Audience members may share photos or quote you, for example via social

media, so don't share anything you wouldn't want to make public. |

| Peer-reviewed journal articles | Projects that follow rigorous research protocols Building the evidence base Long-term impact |

The review and publication timeline is often lengthy. Journals may have concerns or restrictions related to information that is publicly available in another format, such as a white paper. Access may be restricted to the journal's subscribers and people with access through a library. |

The Dissemination Toolkit from the Rural Health Research Gateway provides examples of fact sheets, policy briefs, and other dissemination formats, as well as general guidelines for sharing rural health research findings. Additionally, PCORI offers a Dissemination and Implementation Framework and Toolkit.

It has also become increasingly common for medical and health services researchers to share results with the general public and directly with trial participants, as described in PCORI's Returning Study Results to Participants: An Important Responsibility page. The National Institutes of Health guide, A Checklist for Communicating Science and Health Research to the Public, provides tips for making research results accessible to a wide audience.

Those new to writing about health services research may find the AcademyHealth guide Writing Articles for Peer-Review Publications: A Quick Reference Guide for PHSSR useful. The guide can help those involved in a research project to develop their findings into an article and submit it for publication.

Some well-known and respected publications that accept articles related to rural health topics include:

- The Journal of Rural Health, author guidelines

- Rural and Remote Health, information for authors

- Health Services Research, author guidelines

- Health Affairs, help for authors

- American Journal of Public Health, information for authors and reviewers

Needs Assessment

What are some different types of assessments relevant to rural health?

An assessment seeks to understand the current issues in a community, organization, or program. Rural healthcare facilities and rural communities conduct assessments as a first step in deciding what essential health services best meet the needs of the community. For example, you might assess:

- Comprehensive community health needs, as required for nonprofit hospitals under the Affordable Care Act and for public health agencies seeking Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB) accreditation

- A healthcare facility's attractiveness to potential healthcare providers by identifying facility and community strengths and weaknesses

- The need for a particular healthcare service in a community

- The health status of a particular rural population

- Health needs related to a particular health condition in a rural community

- Rural healthcare workforce supply and demand, for one or many professions

- Social determinants of health that impact overall community health

What are the main steps in planning for and conducting an assessment?

Rural communities planning to conduct an assessment will benefit from thinking about the resources available in their particular community that can support the assessment activities. They can leverage existing relationships and networks, both formal and informal, to gain support and partners in the assessment process. These networks include a wide range of people and programs that impact health, such as clergy, schools, police, Head Start, WIC, and others. They can make use of the healthcare organization or public health newsletter, local newspaper, radio station, and other local media to inform and engage community members. Already scheduled local events, such as regular meetings of service organizations, are another opportunity for weaving the assessment activities into community life.

While the details of an assessment will vary depending upon its purpose, the broad steps are similar:

- Gather the interested parties. Think about and network with other organizations in the community or region. Who else could benefit from the information being gathered? Who should be at the table to address the suspected issues or concerns? Who would be willing to contribute resources?

- As a group, define what is being assessed. What geography? What types of services? Provided to whom?

- Identify the goals of the assessment and the purposes for which you anticipate the findings will be used.

- Locate sources of existing data that can answer questions suggested by the assessment goals.

- Gather information through focus groups, interviews, surveys, and public forums.

- Analyze the results, including the development of maps and other types of reports that show what has been learned. Consider including recommendations for next steps.

- Share the findings.

- Consider making assessment a recurring activity, for example repeating annually or every 3-5 years, rather than a one-time task. Likewise, sharing findings and action steps on a regular basis to engage participants to participate in the future.

The CDC's Community Planning for Health Assessment: Index offers resources for planning assessments for state, tribal, local, and territorial health departments. The Community Toolbox, a free service from the Center for Community Health and Development at the University of Kansas, includes a section on Assessing Community Needs and Resources that describes specific steps in the assessment process.

What are the requirements for nonprofit hospitals to conduct Community Health Needs Assessments (CHNAs)?

The Internal Revenue Service bulletin, Additional Requirements for Charitable Hospitals; Community Health Needs Assessments for Charitable Hospitals; Requirement of a Section 4959 Excise Tax Return and Time for Filing the Return, for nonprofit hospitals includes a requirement to "conduct a community health needs assessment (CHNA) and adopt an implementation strategy to meet the community health needs identified through the CHNA at least once every three years." The IRS bulletin begins with information on how the regulations evolved over time, identifying previous IRS publications that addressed the requirement. The final regulations appear at the end of the bulletin in section §1.501(r)–3 and describe the CHNA requirements in detail.

On an annual basis, hospitals must provide a description of the actions taken during that taxable year to address the needs. The implementation strategy should seek to address the needs identified in the CHNA. In setting forth how it plans to address identified needs, a hospital should:

- Explain what actions it will take and the anticipated impact of the actions,

- Identify the programs and resources it plans to commit, and

- Describe any planned collaboration between the hospital, other providers, and community organizations

See Community Health Needs Assessment for Charitable Hospital Organizations for more information from the IRS on charitable hospital CHNA requirements.

What are the community needs assessment requirements for public health agencies related to the Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB) accreditation standards?

One of the requirements for public health agencies interested in pursuing accreditation is the completion of a community health assessment (CHA) and a community health improvement plan (CHIP). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides an overview of CHA and CHIP requirements, as well as links to more detailed information from the Public Health Accreditation Board. Similar to the CHNA requirements, the CHIP should address the findings from the CHA. For more information about public health department accreditation, see How can a public health department become accredited and what is the process? on the Rural Public Health Agencies topic guide.

How can rural hospitals and public health agencies work together to conduct community assessments?

The IRS requirements of rural nonprofit hospitals are similar to the requirements that local public health agencies must meet to pursue accreditation. In rural communities, the groups with interests in each assessment overlap and the financial resources to undertake a study are limited. It often makes sense for the hospital and public health agency to work together.

A 2012 Public Health Institute report, Best Practices for Community Health Needs Assessment and Implementation Strategy Development: A Review of Scientific Methods, Current Practices, and Future Potential, identifies a number of reasons for rural hospitals and public health to work together, including:

- The large geographic service areas of many rural hospitals and public health agencies may overlap

- Each organization's influence with different groups

- Sharing staff expertise and in-kind resources

- Similar missions and responsibility to community health

- Commitment to collaborate on similar activities

- More likely to have institutional flexibility and history of working together

The PHI report also discusses how public health and nonprofit hospitals can work together to assess community health and plan for improvement. Some of the issues highlighted include:

- The importance of building "shared ownership of community health"

- Addressing differences in the service areas of the hospital and public health agency

- The benefit of collaborating in data collection, which can be resource-intensive

- The roles/involvement of the hospital, public health, and interested groups in setting and addressing priorities

- Collaboration in evaluating community benefit program results, with hospitals potentially benefitting from the evaluation expertise of public health staff

- Jointly sharing findings and progress on improvement plans with the community

What CHNA tools and resources are available for rural facilities?

There are many different CHNA processes available, including examples that have worked well in rural areas. Rural hospitals should consider a range of options to identify an approach that is a good match for their community. Resources for learning about and conducting CHNAs:

- Community Planning for Health Assessment: Index, CDC

- Webinar recording: Understanding the Hospital Community Benefit Requirement and the Community Health Needs Assessment, County Health Rankings and Roadmaps

- Your State Office of Rural Health

- Your State Health Department

Program Evaluation

What are the different purposes that evaluation can serve?

Program evaluations can serve many purposes, all with the goal of continuously improving programs to ensure resources invested in the program and in future programs are well spent. Key purposes are:

-

Process Improvement

Process improvement goes by many names, including process evaluation and formative evaluation. Evaluating the processes and activities are important to understand if a program is implemented as intended. If it isn't, then there is less chance the program will be effective in meeting its goals and objectives and achieving program outcomes. Each step of how the program is supposed to be delivered should be written down. The evaluation then monitors whether each step happened as planned and, if not, provides suggestions for improvement. Rural communities often must adapt programs that have not been previously implemented in a rural area. Evaluating these implementation processes can help fine-tune those adaptations for the rural setting. -

Accountability

A funder often has some minimal data they would like the program to track, such as the number and type of participants and the number and type of activities being conducted. This information doesn't say whether the program is being delivered according to plan or is having its intended impact, but does give the funder a general sense of whether the things they expect to be done are actually done. -

Impact or Effectiveness

Outcome evaluation or summative evaluation focuses on the results the program achieved. The results of an outcome evaluation will help determine what difference the program makes in the long term — its impact. The information gathered can help an organization decide whether it is worthwhile to keep offering the program and help funders decide whether to support the program. The impact of a program will also determine whether other rural communities are likely to want to try a similar intervention.

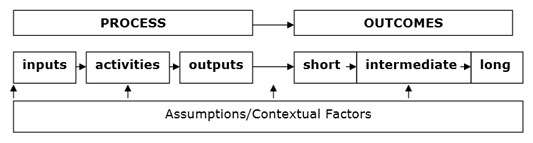

Logic models, also called program roadmaps, are a graphic way to ensure the program assumptions are linked to the activities you are implementing and the outcomes you expect the project to achieve or to which your project is contributing. For example, a project intended to address obesity through a walking club might start with this, which can then be fleshed out into a full logic model:

- Program Assumption – physical activity reduces obesity

- Activity – walking club

- Outcomes – Increased availability of walking clubs, people join and participate in walking clubs, greater frequency and intensity of walking, increased fitness, a 5% reduction in body mass index (BMI) for participating community members.

Logic models don't usually include the measures, or indicators, used to show progress. The logic model is a starting point for what you're trying to achieve, and the indicators are ways you measure and show progress. Having good process and outcome measures is critical.

There are many types and guides for developing logic models. This is a typical logic model layout:

To learn more about logic models:

- Create a Logic Model from the Cottage Center for Population Health

- The Community Toolbox includes a section on developing logic models.

- Tearless Logic Models provides a simplified approach to developing a logic model by answering a series of questions.

- Logic Model: Components and Implementation, a presentation by John Gale of the Maine Rural Health Research Center, provides a general overview of logic model development with a focus on the Flex Program.

Why is it important to evaluate rural health programs?

Rural communities face many challenges related to healthcare delivery and population health but also have limited resources to address these challenges. Program evaluation can help ensure the investment of staff time, organizational will, and other resources are well directed. Program evaluation can also help demonstrate to funders that a program is a worthwhile investment.

Another important reason to evaluate and share the results of rural interventions is to show what works in a rural setting. Many of the evidence-based approaches that federal programs or foundations may request applicants use were demonstrated to work in a non-rural setting. Seeing how well these interventions work, or what adjustments might be needed to make them effective and practical in a rural setting, is a key purpose for evaluating rural health programs. It is also important to share the results of program evaluations through journal publications or other venues, such as those listed in How and where can you share rural health research results? so that other programs can refer to and learn from them as evidence-based practices or promising practices.

How can rural programs plan for and conduct efficient and practical program evaluations?

Rural programs may have limited resources with which to conduct efficient and practical program evaluations. Recommendations for those programs include:

- Plan your evaluation at the outset of the program

- Prioritize the evaluation's focus based on community needs

- Limit the scope of the evaluation

- Select approaches that are easy, appropriate to staff skills and time available, and fit your budget

- Collaborate on the evaluation with project partner organizations

- Consider seeking assistance from a local college or university

For more guidance see the Evaluation on a Shoestring blog post from Australian program evaluator Patricia Rogers on the BetterEvaluation.org website. The CDC offers guidance on program evaluation using the Program Evaluation Framework.

What tools are available to help rural grantees learn about program evaluation?

The State Offices of Rural Health offer program evaluation technical assistance to rural grantees and their partners. Depending on your funding source, you may also be able to get technical assistance through your grant program or funding organization.

Some other sources for learning about program evaluation include:

- Evaluating Rural Programs, in our Rural Community Health Toolkit

- The Community Toolbox section on Evaluating the Initiative

- Evaluating your Community-Based Program, a guide from the American Academy of Pediatrics

- CDC Program Evaluation Framework, which has been used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for over 20 years

- The Step-by-Step Guide to Evaluation: How to Become Savvy Evaluation Consumers, a resource from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation that is free but requires a name and email address to download

How can funders ensure their grantees' experiences help build the collective understanding of what is effective in addressing rural health issues?

Funders can encourage and support their grantees to share their project results and help other rural communities learn about what is effective. Requests for proposals should include requirements and funding to support quality program evaluation. Funders can offer financial support, learning opportunities, and technical assistance to grantees regarding program evaluation.

They can also include funding or provide encouragement to program staff to write up their program results for publication. Publication in a peer-reviewed journal is an important step in making a program or model part of the evidence base. The AcademyHealth guide, Writing Articles for Peer-Review Publications: A Quick Reference Guide for PHSSR, provides guidance on how to develop and submit an article about a health services project for publication.

Funders are in a great position to identify projects that were particularly successful. They can recognize those programs themselves through an award or honor or recommend the projects to other sources that identify model programs. RHIhub, for example, is a resource for sharing and finding programs and approaches that rural communities can adapt to improve the health of their residents. Many of the programs featured in the Rural Health Models & Innovations and Evidence-Based Toolkits were funded by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy.

Another way that funders can make the most of their investments is to work strategically with each other, sharing their grantees' experiences and results. Communication and coordination can also help funders plan and prioritize the projects they choose to support. For example, the Rural Health Philanthropy Partnership (RHPP) is a joint effort of the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP), Grantmakers in Health (GIH), the National Rural Health Association (NRHA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Office of Rural Health (CDC ORH). The collaboration brings together rural federal programs and rural-focused trusts and foundations to work together on key rural health issues. In addition to identifying funding priorities, the group discusses evidence-based metrics to ensure the funded projects are making a difference.

For more on philanthropy and research, see the September 2022 Rural Monitor article Philanthropy, Cross-Collaboration, and the Ecosystem That Is Rural Healthcare Delivery Q&A with Dr. Shao-Chee Sim.