Sep 21, 2022

Philanthropy, Cross-Collaboration, and the Ecosystem That Is Rural Healthcare Delivery: Q&A with Dr. Shao-Chee Sim

Shao-Chee

Sim, PhD, has been Texas-based Episcopal Health

Foundation's vice president for research, innovation,

and evaluation since 2015. A first-generation immigrant,

he and his family settled in New York City. Later, his

academic pursuits in policy work provided

culture-specific research opportunities that eventually

led him to the philanthropic work that includes rural

healthcare delivery. Additionally, Sim serves on several

boards, including the National Rural Health

Resource Center board.

Shao-Chee

Sim, PhD, has been Texas-based Episcopal Health

Foundation's vice president for research, innovation,

and evaluation since 2015. A first-generation immigrant,

he and his family settled in New York City. Later, his

academic pursuits in policy work provided

culture-specific research opportunities that eventually

led him to the philanthropic work that includes rural

healthcare delivery. Additionally, Sim serves on several

boards, including the National Rural Health

Resource Center board.

Share with us your background and the career trajectory that took you to Episcopal Health Foundation (EHF), including how your rural health interest developed.

My family and I immigrated to New York City around 1986 and my early career years were spent there. I have a PhD in public policy and my dissertation focused on health economics related to the impact of federal substance abuse and mental health block grants on state and local government spending.

In the aftermath of Sept. 11, 2001, I was asked to study the economic impact of the tragedy on Manhattan Chinatown and the mental health effects of victim families. These projects launched my career in research and policy work. When I started working with the large New York City Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) in 2008, I developed interest in not just the operational issues of healthcare delivery systems, but the issues around access to primary care… Since 2015, I've been the vice president of research, innovation, and evaluation at Episcopal Health Foundation and there I began to focus on rural healthcare delivery. We're located in Houston, but also serve Austin, Waco, Tyler and areas across central, west and southeast Texas. Our service area includes 57 counties — 42 of which are rural.

Would you share one of your most impactful rural EHF projects to date?

In 2016, Houston and Trinity counties closed their rural hospitals within several months of each other. Of course, emotions were high and residents didn't understand why their hospitals couldn't continue service. We at the foundation asked ourselves, "What can we do immediately? Could we make emergency short-term grants? What other options are there?"

After further conversation, we realized that type of support would not be enough to allow for a reorganization geared to sustainability. However, those discussions were still dichotomous: What could we do now and what is our long-term interest in rural healthcare delivery? To start, we realized we needed to better understand those rural communities.

As we considered our role and how we could add value, we decided we needed specific data. To get that data required EHF to fund targeted research. I connected with others, internally within the foundation, and externally with experts across the state. Specifically, I approached Dr. Nancy Dickey at Texas A&M University. Our collaboration with her produced EHF's first report on Texas rural hospital closures. The results were very much in sync with our early thinking at EHF — it's time to figure out how best to optimize rural healthcare delivery.

With information from that report, we recognized that in some communities, rural healthcare would be delivered by hospitals. In others, it might be better delivered through pharmacies, stand-alone emergency rooms, or something like a health resource center.

Around that time, I realized the need to re-examine why the current rural healthcare system was in place. In one related meeting with other funders, I remember sharing that the federal law [Public Law 1946 PL 79-725 with the Hill-Burton Program] that helped build hospitals in rural communities in the 1950s was a post-World War II law. It passed in a period when the notion existed that every neighborhood and every community needed a hospital. For some rural stakeholders, the mindset behind that public law remains.

I believe policy conversations now must include a reframing around what each community needs for their healthcare delivery system — and we need to give communities freedom and flexibility to figure that out.

Yet, times have changed. Medicine has changed. I believe policy conversations now must include a reframing around what each community needs for their healthcare delivery system — and we need to give communities freedom and flexibility to figure that out. They should not feel that the only option is either have or not have a hospital. There is a continuum of care they can choose from.

Again referencing those valuable results from our first rural research project, we realized we needed to have more data for a broader knowledge of the issues around rural hospital closures. I reached out to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the TLL Temple Foundation. They, too, were willing to support further research. That led to Phase II of Dr. Dickey's work. It provided a perspective based on three case studies and the analysis included interviews with community residents and hospital leadership, specifically hospital board members.

Both research projects were impactful for two reasons. First, the research provided the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy with vital information that could be included for a national technical assistance grant for vulnerable rural hospitals. The program's first grantee was Dr. Dickey and the team at the Center for Optimizing Rural Health.

The second reason is that those two research projects also demonstrated the power of cross-funder collaboration that I've subsequently written about. It's been really rewarding for us at EHF to see our small initial research project have larger impact on the national level.

How do philanthropic-supported research efforts impact rural health?

Philanthropic-supported research efforts impact rural health because foundations are nimble, responsive, and we are also boots-on-the-ground.

Philanthropic-supported research efforts impact rural health because foundations are nimble, responsive, and we are also boots-on-the-ground. For example, during those two county rural hospital closures, I kept up by reading the local rural newspaper coverage. Those three characteristics make foundations unique in a rural area. Compared to state or federal grant funding, we can also offer quick turnaround for research funding.

Another impact comes from the fact that we don't just support research, we communicate research results. I believe that this communication is equally important to the research itself. Again, with our Texas hospital closure research, we were able to connect with the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy. The agency was very open to hearing our results. We also presented our reports at rural health organizations' annual meetings. These types of activities generate a lot of conversation and allow us to convey our work to many rural stakeholders.

When I think about philanthropic-supported research, I also think about another distinction: Investment in research also allows us to inform policy-making and programmatic decisions.

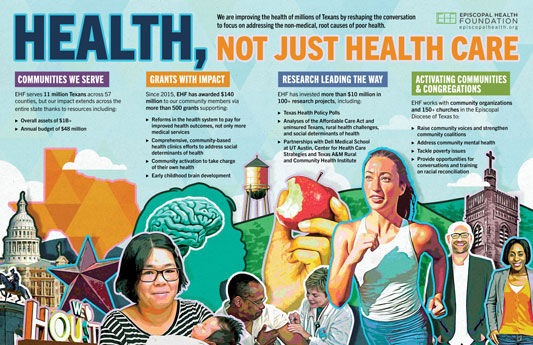

One of Episcopal Health Foundation's strategies is centered in #HealthNotJustHealthCare. What are the foundation's current rural health strategies for its service area?

Access to healthcare is one area that we are looking at — but looking at it to address it in different ways. For example, in the context of keeping a hospital open, asking if there are other equally important service delivery models. In the last couple of years, we're thinking about rural communities that don't have enough service demand to keep a clinic or hospital open. We need to meet those communities where they are, talk to them about other ways to meet their healthcare needs. A community resource hub may be an option, but that means it will also be a new way of doing the business of healthcare.

We also know that those strategies are all about community engagement. We want to do things reflective of the community members' needs, wants, and preferences. We want to help find ways for communities to take charge of their own health. One of Dr. Dickey's major research findings was that sometimes hospital board members did not know what was happening in their hospital. At other times, they knew, but were unable to communicate to their communities what was happening. This latter situation definitely speaks to the need for community engagement.

What community engagement keys are successful in Texas, and, perhaps with modification, useful for the rest of rural America?

Community engagement is key for innovation. Actually, it implies replication because it's really a continuum for capacity building for whatever the need, from faith-based needs to healthcare needs. At EHF, we have a grantmaking division and a community engagement division with full time staff that are out there helping church members and community members talk through the continuum that involves consultation, evolution, collaboration, and shaping of leadership.

Is there another specific example of the Foundation's current work in Texas that is poised to potentially influence innovation in other rural areas of the country as did the work around Texas rural hospital closures?

EHF's board very recently approved funding to support the Texas Health and Human Services Commission in implementing the CHART model in Texas. As you know, this model — the Community Health Access and Rural Transformation — is a CMS [Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services] Innovation Center model. Texas is one of four state participants, along with Alabama, South Dakota, and Washington. This model looks at ways to provide support to hospitals wanting to venture into the value-based purchasing payment alternative as a way to remain in business over the long term. The model includes telemedicine offerings, but is also mindful of the social determinants of health and population health management.

When hesitancy and uncertainty exist on the part of rural health stakeholders …, foundations are often willing to step in and take some risk to support promising innovations.

No one knows if CHART will work. When hesitancy and uncertainty exist on the part of rural health stakeholders around this type of investment, foundations are often willing to step in and take some risk to support promising innovations. As one of those foundations, we're looking at this work with the Commission as an opportunity to add value and support to the overall effort.

We also see a role in working to get other funders involved with projects like this. I see immense value in this type of work. Even small investments in rural-focused research has had such a huge return on investment. It's been incredible.

Philanthropy leaders are often thought of as thought leaders, or as futurists. Imagining yourself in those roles, what would you personally consider most important if specifically tasked with modernizing rural healthcare delivery?

Funders need to be able to think outside the box and take bold steps. And do that despite the knowledge that everything will not always work out the way it's intended. We are in the business of investing and in taking risks. We are also in the business of evaluating outcomes and learning from the work we've supported.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we have lived through huge changes in healthcare technologies. This provides room for creativity and experimentation in the area of rural healthcare delivery and is actually one of the reasons we got very interested in supporting CHART. Hearing from folks at our state rural health organizations, we've learned that many rural hospital leaders are concerned about changing from the fee-for-service model to a capitated payment model. They're very comfortable with fee-for-service. But with that system, they are also struggling with their bottom line. To explore an alternative payment system will require a whole new mindset — and culture. These changes will require both top-down and bottom-up education that will lean on community engagement.

What are two important issues for rural health and/or rural healthcare delivery that our audience might not have yet considered or heard about, but might be important for their future efforts?

The first issue I've mentioned several times and I want to emphasize again: the role of data and research for future efforts to support change in rural health. We are not in the business of funding for the sake of knowledge alone. We are in the business of supporting research because we need it to make improvement in rural healthcare delivery — and improvements that have real impact on people's lives. Whether you are coming from a perspective as a hospital leader or state policymaker or a foundation, you must have data and research to help inform your decision-making.

Rural healthcare delivery is a complex issue. You need to ask the entire community and the entire ecosystem to think with you.

The second theme I'd like to emphasize is an issue of being involved behind the scenes. As I reflect on my experience, it's really about how you see yourself in this larger ecosystem of rural healthcare delivery. In what ways could you be strategic or be intentional? In my case, it's about taking advantage of your existing network. For example, I was able to talk with rural-focused federal agency connections on one side and other philanthropic health funder connections on another side. I like being a connector and leveraging all my relationships. Rural healthcare delivery is a complex issue. You need to ask the entire community and the entire ecosystem to think with you.

Opinions expressed are those of the interviewee and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Rural Health Information Hub.