Rural Healthcare Workforce

Maintaining the healthcare workforce is fundamental to providing access to quality healthcare in rural areas. Rural healthcare facilities must employ enough healthcare professionals to meet the needs of the community. They should have adequate education and training and hold appropriate licensure or certification. When facilities promote coordination between health professionals and place them in roles where their skills can be used to best advantage, patients will receive the best possible care.

Strategies for optimizing the use of health professionals in rural areas include:

- Using interprofessional teams to provide coordinated and efficient care for patients and to extend the reach of each provider.

- Ensuring that all professionals are practicing to the full extent of their training and allowed scope of practice.

- Removing state and federal barriers to professional practice, where appropriate.

- Changing policy to allow expansions to existing scopes of practice if evidence shows that the healthcare workers can provide comparable or better care.

- Removing barriers to the use of telehealth to provide access to remote healthcare providers.

As the United States struggles with shortages of healthcare providers, an uneven distribution of workers means that shortages are often more profound in rural areas. This maldistribution is a persistent problem affecting the nation's healthcare system.

This guide examines policy, economics, planning challenges, and issues related to rural health workforce, including:

- Supply and demand

- Distribution of the workforce

- Characteristics of the rural healthcare workforce

- Licensure, certification, and scope of practice issues

- Programs and policies that can be used to improve the rural healthcare workforce

For additional information on rural healthcare workforce issues, see these RHIhub topic guides:

- Recruitment and Retention for Rural Health Facilities

- Education and Training of the Rural Healthcare Workforce

Frequently Asked Questions

- Is there a healthcare workforce shortage in rural areas?

- What is a Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA)?

- How are HPSA designations determined?

- Where are HPSAs located in rural areas?

- What are Medically Underserved Areas (MUAs), Medically Underserved Populations (MUPs), and Governor-Designated Secretary-Certified Shortage Areas for Rural Health Clinics?

- How do the distribution and characteristics of the healthcare workforce compare across rural and urban areas?

- What state-level policies and programs can help address the shortages in the rural healthcare workforce?

- What can schools do to meet rural healthcare workforce needs?

- What strategies can rural healthcare facilities use to help meet their workforce needs?

- How do international medical graduates help fill rural physician workforce gaps?

- Where can I find statistics on healthcare workforce for my state, including data on employment, projected growth, and key environmental factors?

- What are some federal policies and programs designed to improve the supply of rural health professionals?

- Where can states get technical assistance for health workforce planning, including how to address rural needs?

Is there a healthcare workforce shortage in rural areas?

Workforce shortages are very common in rural communities. It should be noted, however, that there is variation among rural communities when it comes to the adequacy of their health workforce supply. Some communities rarely experience health workforce supply problems, while others experience persistent shortages of health professionals.

The Council on Graduate Medical Education report Strengthening the Rural Health Workforce to Improve Health Outcomes in Rural Communities, published in 2022, noted that rural hospital closures have reduced access to healthcare in some rural communities, and that workforce shortages are a problem even in areas that have retained their healthcare facilities. The report goes on to say that the COVID-19 pandemic has had the effect of exacerbating pre-pandemic shortages, leading to high levels of staff burnout, high turnover, and exposure to infection.

Whether shortages exist in rural communities and how severe they are can be difficult to determine since estimates of supply and demand for specific professions are not always available. The Health Resources and Services Administration's Workforce Projections Dashboard shows projections of the supply of and demand for healthcare workers across the United States. This tool incorporates factors such as changing population size, demographics, new entrants and exiting providers in various occupations, and differing levels of access to care.

Maldistribution of healthcare professionals is also a problem affecting rural communities. The Association of American Medical Colleges document The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2021 to 2036 notes that if underserved populations had healthcare use similar to populations with fewer sociodemographic, economic, and geographic barriers, 117,100 to 202,800 additional physicians would be needed by 2036.

The following factors were identified in an interview with WWAMI Rural Health Research Center researchers and in various NRHA policy documents:

- Education

- The current healthcare education system tends to be urban-centric.

- Access to healthcare training and education programs may be limited in rural areas, particularly beyond the community college level.

- Providers trained in urban areas may not be prepared for the challenges of working in rural communities or the kinds of health concerns rural patients may present.

- Urban areas frequently draw potential healthcare professionals away from rural areas. Students in rural communities may have to travel or relocate to an urban area for health professions coursework, unless they can find degree programs offered online, or for clinical training. Some do not return to rural communities after completion of their studies.

- There are fewer clinician role models in rural communities.

- Rural secondary school students may have fewer opportunities to take advanced math and science courses needed to pursue health careers.

- Rural Demographics and Health Status

- Rural populations usually have higher rates of chronic illness, which creates more demand.

- Rural areas tend to have higher proportions of older residents, who typically require more care.

- Rural populations tend to be poorer and may forego care due to cost.

- Rural Practice Characteristics

- When rural communities lack certain types of providers, particularly specialists, patients must travel longer distances or forego care if telehealth services are not available or an appropriate option.

- Barriers such as reimbursement policies and lack of broadband availability have hindered telehealth adoption in some rural areas.

- Rural communities may offer fewer opportunities for career advancement.

- Understaffing causes increased workloads, longer shifts, and less flexibility in scheduling, which may lead to healthcare provider burnout and be detrimental to the recruitment and retention of clinicians.

- Economics

- Urban facilities and practices may offer higher salaries, more benefits, and better working conditions.

- Health professions that require longer and more expensive training can be less affordable for rural students.

- It may be difficult for providers to find adequate housing.

What is a Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA)?

HPSA designations indicate shortages of healthcare professionals who provide primary care, dental, and mental health services. HPSAs are designated by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). A detailed description of HPSAs can be found at the HRSA Bureau of Health Workforce's Types of Designations page. HPSAs may be:

- Geographic, based on the population of a defined geographic area

- Population-specific, for a subset of the population in a defined geographic area, such as those whose incomes are at or below 200% of the federal poverty level

- Facility-based, such as public or nonprofit private clinics, state mental health hospitals, and federal or state correctional facilities

In addition, there are safety net clinics that automatically receive shortage designation status. These include:

- Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and FQHC Look-Alikes

- Indian Health Service and tribal clinics

- Rural Health Clinics (RHCs) – must complete a Verification of Clinic Data, CMS Form-29 that certifies the RHC meets all NHSC site requirements.

Maternity Care Target Areas (MCTA) are geographic areas within existing HPSAs that have shortages of maternity care professionals. Final criteria for MCTAs were published by HRSA in May 2022.

How are HPSA designations determined?

State Primary Care Offices are responsible for conducting needs assessments to determine which areas within their states should be considered shortage areas. They then submit applications to HRSA for review. For a fuller explanation of the process, see the HRSA Bureau of Health Workforce's Reviewing Shortage Designation Applications page. The primary factor used to determine whether a location may be designated as a HPSA is the number of full-time equivalent healthcare professionals relative to the population, with consideration given to high-need indicators such as a high percentage of the population living at or below 100% of the federal poverty level. See Scoring Shortage Designations for information related to the criteria and calculations HRSA uses to determine HPSAs.

Where are HPSAs located in rural areas?

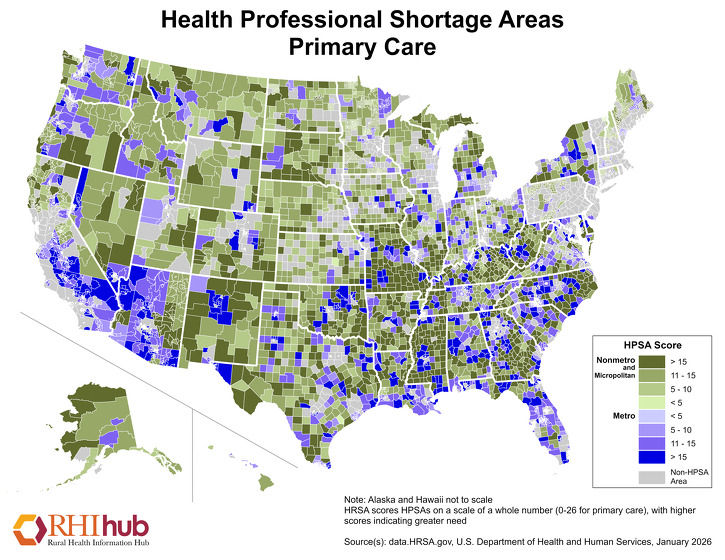

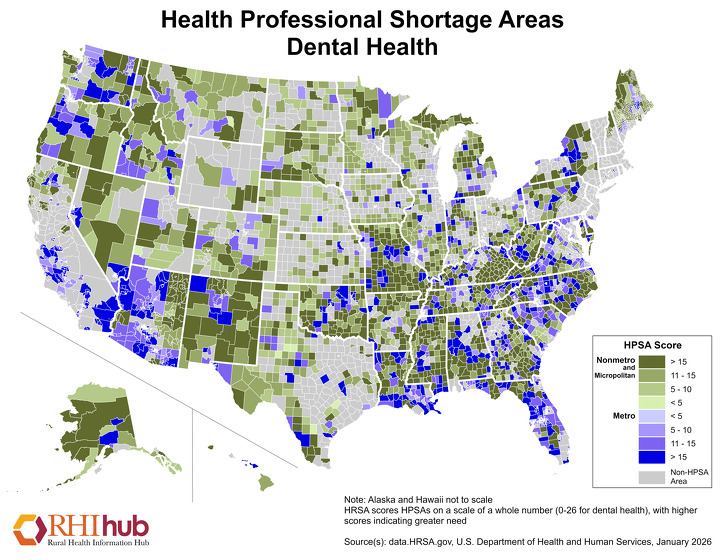

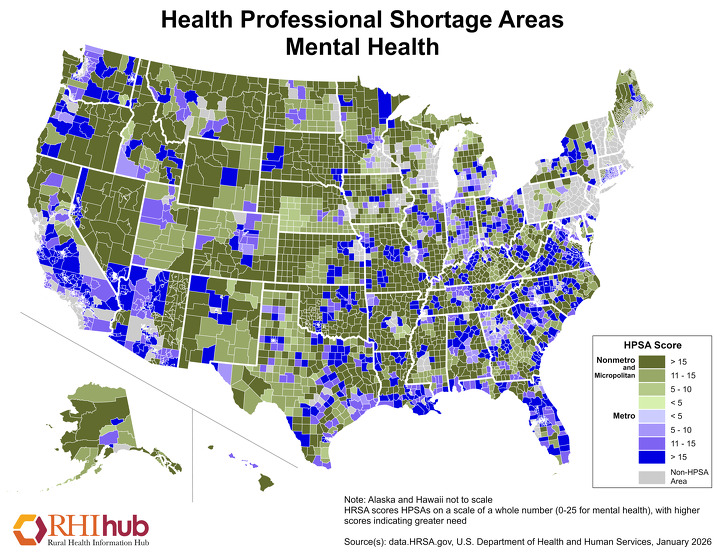

According to State of the Primary Care Workforce, 2025, 63.1% of primary care HPSAs are in rural areas. The following maps show designated HPSAs for primary care, dental health, and mental health, as of January 2026. Higher scores indicate greater need.

To search for HPSAs by state and county, see HRSA's HPSA Find tool. For statistics on HPSAs, including national percentages of HPSAs located in rural and urban areas, see the data.HRSA.gov Designated Health Professional Shortage Areas Statistics.

What are Medically Underserved Areas (MUAs), Medically Underserved Populations (MUPs), and Governor-Designated Secretary-Certified Shortage Areas for Rural Health Clinics?

Medically Underserved Areas (MUAs) and Medically Underserved Populations (MUPs) are federal shortage designations that indicate a lack of primary care services for an area or a population. Governor-Designated Secretary-Certified Shortage Areas for Rural Health Clinics are areas with provider shortages, as identified by a state governor or designee. MUAs and MUPs are based on four factors:

- Ratio of population to primary care providers

- Infant mortality rate

- Percentage of population at or below the federal poverty level

- Percentage of population age 65 or older

A list of MUAs and MUPs can be found at HRSA's Data Explorer. To search for MUAs and MUPs by state and county, visit HRSA's website, MUA Find.

For further information on MUA/MUP designations, see What is a Medically Underserved Area/Population (MUA/P)? on the HRSA website or contact your state Primary Care Office.

How do the distribution and characteristics of the healthcare workforce compare across rural and urban areas?

The following table shows ratios of health professionals per 10,000 population in rural areas as compared with urban areas for select professions. With the exception of Licensed Practical Nurses/Licensed Vocational Nurses, the supply of every type of health professional is lower in rural than urban areas:

| Occupation | Nonmetro | Metro |

|---|---|---|

| 2024 – BLS Occupational Employment Statistics | ||

| Registered Nurses (RNs) | 65.1 | 99.5 |

| Licensed Practical and Licensed Vocational Nurses (LPNs/LVNs) | 21.3 | 17.8 |

| 2023 – HRSA Area Health Resource Files | ||

| Dentists | 4.8 | 7.9 |

| Physician Assistants (PAs) | 3.5 | 5.6 |

| Nurse Anesthetists | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| Nurse Practitioners (NPs) | 9.5 | 12.1 |

| Total Advanced Practice Registered Nurses | 11.1 | 14.4 |

| 2022 – HRSA Area Health Resource Files | ||

| Physicians (MDs) | 11.0 | 33.0 |

| Physicians (DOs) | 2.0 | 3.1 |

| Primary Care Physicians | 5.1 | 8.0 |

| Total Physicians | 13.0 | 36.0 |

Rural Primary Care Physicians

According to the HRSA research brief State of the Primary Care Workforce, 2025, there are lower ratios of primary care physicians in rural communities than in urban areas, and as of 2023, 7.2% of counties had no primary care physicians. The American Enterprise Institute document Nurse Practitioners: A Solution to America's Primary Care Crisis notes that, between 2000 and 2016, the number of primary care physicians practicing in rural areas decreased by 15%, and this decline is expected to continue through 2030.

Rural Obstetrical Care Workforce

The WWAMI Rural Health Research Center's policy brief, The Supply and Rural-Urban Distribution of the Obstetrical Care Workforce in the U.S., notes that rural areas have seen a decrease in access to maternal care in recent years, due in large part to closure of obstetric units and a shortage of healthcare professionals who deliver babies. Significantly fewer obstetricians serve nonmetro counties, per 100,000 women of childbearing age, compared to metropolitan counties. However, family physicians are more likely to deliver babies as the rurality of the county in which they practice increases. The HRSA report, State of the Primary Care Workforce, 2025, says that a significant and increasing amount of obstetric care in the United States is being provided by primary care physicians.

| Occupation | Providers per 100K women of childbearing age, Metropolitan | Providers per 100K women of childbearing age, Nonmetropolitan |

|---|---|---|

| Obstetricians | 60.3 | 35.1 |

| Advanced Practice Midwives | 11.3 | 8.7 |

| Midwives | 5.2 | 5.6 |

| Family Physicians Who Deliver Babies | 9.8 | 34.4 |

| Source: The Supply and Rural-Urban Distribution of the Obstetrical Care Workforce in the U.S. | ||

Rural Physician Assistants (PAs)

State of the Primary Care Workforce, 2025 notes the importance of PAs and nurse practitioners (NPs) in rural healthcare and says that 44% of PAs were practicing in or interested in practicing in rural areas. The same report notes that there is expected to be a surplus of PAs overall by 2038. According to a June 2020 report, Supply and Distribution of the Primary Care Workforce in Rural America: 2019, from the WWAMI Rural Health Research Center, as of 2019 there were 24.1 PAs per 100,000 population in non-core counties, as compared with 32.3 in micropolitan areas and 42.5 in metropolitan areas. The same report notes that the number of PAs being trained is increasing at a higher rate than that of primary care physicians, indicating that numbers of PAs providing primary care in rural areas will continue to grow.

Rural Nurse Practitioners (NPs)

According to the same June 2020 report, Supply and Distribution of the Primary Care Workforce in Rural America: 2019, from the WWAMI Rural Health Research Center, as of 2019 there were 55.2 NPs per 100,000 population in non-core counties, as compared with 64.6 in micropolitan areas and 69.5 in metropolitan areas. Between 2010-2016, the NP workforce grew by 9.4%, thus increasing the number of NPs who might choose to work in rural areas.

Rural Registered Nurses (RNs)

The 2021 Journal of Professional Nursing article Rural-Urban Differences in Educational Attainment Among Registered Nurses: Implications for Achieving an 80% BSN Workforce notes that urban nurses were more likely to have a BSN degree than rural nurses (57.9% versus 46.1%). In a survey of 34,104 nurses from all 50 states, the researchers found that rural nurses on average:

- Were slightly older than urban nurses (43.5 versus 42.9 years)

- Had a shorter commute (22.9 versus 24.4 minutes)

- Had lower salaries ($51,361 versus $55,807)

The same study found that the majority of nurses work in hospitals, irrespective of rural or urban setting, and a higher percentage of rural nurses worked in skilled nursing facilities than urban nurses (12.7% versus 8.2%).

According to the Bureau of Health Workforce's document Nurse Workforce Projections, 2022-2037, nonmetro areas are expected to outpace metro areas in shortages of RNs in the next three interval years of 2027 (24% vs. 7%), 2032 (19% vs. 6%), and 2037 (13% vs. 5%).

Rural Licensed Practical Nurses (LPNs)

According to an April 2024 article from the Journal of Nursing Regulation, rural LPNs are:

- Similar in age to urban LPNs – The average age of rural LPNs is 47.2 and urban LPNs is 48.0.

- Less likely to be male – About 10% of rural LPNs are male, whereas 12% in urban areas are male.

Rural Behavioral Health Professionals

The WWAMI Rural Health Research Center's report Changes in the Supply and Rural-Urban Distribution of Counselors in the U.S., 2014-2021 notes that there are only about two-thirds as many counselors per 100,000 population in rural U.S. counties than in metropolitan centers.

The following chart shows rates of providers in rural areas as compared with urban areas for selected behavioral health professions:

| Occupation | Providers per 100K, Metropolitan | Providers per 100K, Nonmetropolitan |

|---|---|---|

| Psychiatrists (2019) | 13.0 | 3.5 |

| Psychologists (2021) | 39.5 | 15.8 |

| Social Workers (2021) | 96.4 | 57.7 |

| Psychiatric Nurse Practitioners (2021) | 4.8 | 3.4 |

| Counselors (2021) | 131.2 | 87.7 |

| Sources: Changes in the Supply and Rural-Urban Distribution of Psychiatrists in the U.S., 1995-2019; Changes in the Supply and Rural-Urban Distribution of Psychologists in the U.S., 2014-2021; Changes in the Supply and Rural-Urban Distribution of Social Workers in the U.S., 2014-2021; Changes in the Supply and Rural-Urban Distribution of Psychiatric Nurse Practitioners in the U.S., 2014-2021; Changes in the Supply and Rural-Urban Distribution of Counselors in the U.S., 2014-2021, WWAMI Rural Health Research Center, 2022 | ||

What state-level policies and programs can help address the shortages in the rural healthcare workforce?

Funding options that states can use to address rural health workforce include:

- Supporting healthcare education and recruitment to rural areas through grants, loans, fellowships, scholarships, state loan repayment/forgiveness or scholarship programs, faculty loan repayment programs, tax benefits, and other incentives

- Increasing the number of healthcare graduates prepared for rural practice produced by state schools, by supporting the development and growth of healthcare education programs with rurally-oriented curricula

- Supporting rural clinical training opportunities, including residency programs

Policy options that states can use to address rural health workforce shortages include:

- Removing barriers to practice, such as allowing telehealth services to be provided across state lines

- Allowing new or alternative provider types to practice in rural areas

- Expanding existing scopes of practice

- Expediting licensure of new healthcare professionals and reactivation of expired licenses

What can schools do to meet rural healthcare workforce needs?

Health professions schools can:

- Use admissions criteria that are likely to produce providers interested in rural practice, such as admitting more students from rural communities or who intend to practice in a rural community

- Offer rural-centric curricula and training tracks

- Develop distance education programs

See the Education and Training of the Rural Healthcare Workforce for more information.

What strategies can rural healthcare facilities use to help meet their workforce needs?

Rural healthcare facilities can employ various strategies to ease healthcare workforce shortages and improve care. For instance, they can use technology, such as telehealth, to fill gaps in care caused by shortages. In addition, facilities can use interprofessional care teams to provide more efficient and high-quality care and can participate in educating rural healthcare professionals through offering clinical training experiences.

Redesigning practice and processes to allow professionals to work at the top of their license and skill set can also lessen the effects of shortages. Facilities could provide opportunities for workers to learn new skills and encourage them to pursue career advancement through apprenticeships and other educational opportunities.

Rural areas often experience difficulties related to recruitment and retention of primary care and other health professionals. Thus, it is important to plan for future workforce needs. By anticipating retirements and departures of staff, administrators can take steps to recruit replacements in a timely manner, and avoid prolonged vacancies at their facilities. Increasing pay, benefits, flexibility, and opportunities for career advancement might also improve chances for success with recruitment and retention.

For ideas on recruiting and retaining healthcare professionals, see the Recruitment and Retention for Rural Health Facilities guide.

How do international medical graduates help fill rural physician workforce gaps?

Many rural communities recruit international medical graduates with J-1 visa waivers to fill physician vacancies. The Conrad State 30 Program allows each state's health department to request J-1 Visa Waivers for up to 30 foreign physicians per year. The physicians must agree to work in a federally designated Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) or Medically Underserved Area (MUA). Interested parties should contact the Primary Care Office in the state where they intend to work, for more information and exact requirements. See the Rural J-1 Visa Waiver topic guide for details.

In addition to the J-1 visa waiver, non-immigrant H-1B visas are sometimes used to fill employment gaps. These are employer-sponsored visas for "specialty occupations," including medical doctors and physical therapists. H-1B visas are issued for three years and can be extended to six years. For more information, see the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration pages on the H-1B Program and H-1B Specialty Occupations.

Where can I find statistics on healthcare workforce for my state, including data on employment, projected growth, and key environmental factors?

HRSA's National Center for Health Workforce Analysis provides in-depth data on supply, demand, distribution, education, and use of health personnel.

The National Forum of State Nursing Workforce Centers provides a list of state nursing workforce center initiatives throughout the nation.

HRSA's Area Health Resources Files (AHRF) provides demographic and training information on more than 50 healthcare professions.

The U.S. Department of Labor's Occupational Employment Statistics: May 2023 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates provides state-level information on occupational employment within "Healthcare Practitioners and Technical Occupations" and "Healthcare Support Occupations."

The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC)'s U.S. Physician Workforce Data Dashboard provides data on physician supply, medical school enrollment, and graduate medical education throughout the United States.

The Kaiser Family Foundation's State Health Facts: Providers & Service Use Indicators provides data on physicians, RNs, PAs, NPs, dentists, and healthcare employment.

The Robert Graham Center's Workforce Projections provides primary care physician workforce projection reports for all states.

What are some federal policies and programs designed to improve the supply of rural health professionals?

Area Health

Education Centers (AHEC) Program

AHECs promote interdisciplinary, community-based training initiatives intended to improve the distribution,

supply, and quality of healthcare personnel, particularly in primary care. The emphasis is on

delivery sites in rural and underserved areas. AHECs act as community liaisons with academic institutions and

assist in arranging training opportunities for health professions students, as well as K-12 students.

National Health Service Corps (NHSC)

NHSC offers scholarships and loan repayment programs, which can enable students to complete health professions

training. Students must agree to complete a service commitment in a Health Professional Shortage Area. According

to the infographic Building

Healthier Communities, approximately 1 in 3 NHSC clinicians works in rural areas. This represents

more than 3,000 primary care clinicians, more than 3,400 clinicians working in the areas of mental and

behavioral health,

and almost 700 dental clinicians.

Teaching

Health Center Graduate Medical Education (THCGME)

Program

The THCGME program supports students in primary care residency training programs in community-based ambulatory

patient care centers. There are two types of awards: Expansion awards for increasing the number of resident

full-time equivalent positions at existing HRSA THCGME programs and new awards to support new resident FTE

positions at new Teaching Health Centers.

Teaching Health

Center Planning and Development (THCPD)

This program makes awards to establish new accredited community-based primary care medical or dental residency

programs to address shortages in the primary care physician and dental workforce and to address challenges faced

in rural and underserved communities.

Rural Residency

Planning and Development (RRPD) Program

The RRPD program provides funding to create new rural residency programs. Grants of up to $750,000

are provided to cover direct and indirect costs for accreditation, faculty development, and resident

recruitment.

For more information see Scholarships, Loans, and Loan Repayment for Rural Health Professions.

Where can states get technical assistance for health workforce planning, including how to address rural needs?

The Health Workforce Technical Assistance Center (HWTAC) offers technical assistance to states and organizations involved in health workforce planning. HWTAC activities can include:

- Direct technical assistance

- Educational webinars

- Facilitating access to health workforce data

HWTAC is a partnership of the Center for Health Workforce Studies (CHWS) at the School of Public Health, University at Albany, State University of New York and the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina. It is funded by HRSA's Bureau of Health Workforce.