Health and Healthcare in Frontier Areas

Frontier areas are the most remote and sparsely populated places along the rural-urban continuum, with residents far from healthcare, schools, grocery stores, and other necessities. Frontier is often thought of in terms of population density and distance in minutes and miles to population centers and other resources, such as hospitals. Frontier areas may be defined at the community level by county, ZIP code or census tract; however, they are most often delineated by county.

Many frontier counties are located in the West, a part of the country where individual counties tend to cover a large geographic area. Even counties that have a town with a hospital, grocery store, and other services may also encompass areas that are much more rural and isolated, making them frontier counties. Frontier areas face unique challenges to providing access to health and human services compared to most other rural communities.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is the definition of frontier?

- How much of the U.S. is frontier?

- How can I find out if my county is a frontier county?

- What are some of the healthcare challenges in frontier areas?

- What health-related infrastructure challenges are unique to frontier areas?

- How does government ownership of large tracts of land affect the ability to provide services in frontier areas?

- Are there funding or reimbursement advantages to being considered a frontier area?

- What types of models have been developed to address frontier healthcare issues?

- What are some examples of workforce models that have been used to address healthcare issues in frontier areas?

What is the definition of frontier?

In general, frontier areas are sparsely populated rural areas which are isolated from population centers and services. Unfortunately, there is not a single universally-accepted definition of frontier. Definitions of frontier used for state and federal programs vary, depending on the purpose of the project being researched or funded.

While frontier is often defined as counties having a population density of six or fewer people per square mile, this simple definition does not take into account other important factors that may isolate a community. Therefore, other definitions are more complex and address isolation by considering distance in miles and travel time in minutes to services. A 2016 policy brief from the National Rural Health Association (NRHA) identifies several factors that may be considered in classifying an area as frontier including:

- Population density

- Distance from a population center or specific service

- Travel time to reach a population center or service

- Functional association with other places

- Availability of paved roads

- Seasonal changes in access to services

Frontier may be defined at the community level by county, ZIP code, census tract, or other defined geographic unit. What is Frontier?, a publication of the National Center for Frontier Communities (NCFC), defines frontier using a composite of population density, travel time, and distance to market and service centers:

- Density of between 12 and 20 persons per square mile

- Distance to a service/market between 30 and 90 miles

- Travel time to service/market between 30 and 90 minutes

Other commonly used definitions include:

Rural-Urban Commuting Areas (RUCAs)

Rural-Urban Commuting

Areas (RUCAs) can be used to identify very remote areas, which could be considered frontier-like due to

their isolation from population centers. Under the RUCA definition, types of rural and urban are defined by

proximity to urban areas and the portion of the population that commute for work from place to place. For

instance, a RUCA code of 10 is assigned to isolated, small rural census tracts, whereas a RUCA code of 1 is

assigned to urban areas. RUCAs are available by census tract and ZIP code area.

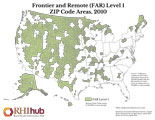

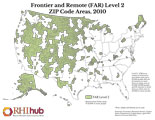

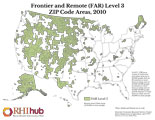

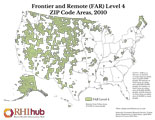

Frontier and Remote (FAR) Codes

The USDA Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS) and the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy

(FORHP) developed the Frontier and Remote (FAR) area codes to be used in research and policymaking. The FAR

codes methodology uses urban-rural data from the 2010 Census population and urban area boundaries. Using

population size, distance, time and geographic units, this methodology produces 4 distinct FAR categories,

allowing the user to determine how inclusive to be in designing their legislation, regulations, programs, or

research.

The 4 FAR levels are determined by population density of an area combined with the distance from urban areas where they can access goods and services.

Information and maps on the methodology are available at USDA Economic Research Service: Frontier and Remote Area Codes.

Other frontier definitions include:

CMS Super Rural

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) provides enhanced ambulance service reimbursement in areas

it designates as super rural. This definition identifies these frontier areas as the bottom quartile of

nonmetropolitan ZIP codes by population density.

BPHC Sparsely Populated Areas Criterion

The Bureau of Primary Health Care (BPHC) uses population density as a method to identify frontier service areas

eligible for funding priority. BPHC defines a sparsely populated area as any service area with a population

density no greater than 7 persons per square mile for the entire service area.

How much of the U.S. is frontier?

The number of people living in the frontier and the amount of land that is frontier will vary depending on the definition of frontier used. In 2011, the National Center for Frontier Communities (NCFC) asked each of the State Offices of Rural Health (SORH) to designate which of their state's counties were frontier. The SORHs designated 46% of the land area of the United States as frontier, and over 5.6 million people lived in these areas in 2010.

According to the most recent RUCA codes, in 2010 9.9 million people lived in a census tract with a RUCA code of 10, which is assigned to the most isolated, small rural census tracts. If using Frontier and Remote (FAR) area code methodology, 12.2 million people were living in level 1 territory (the least restrictive frontier delineation) and 2.3 million resided in level 4 (the most restrictive delineation). Please refer to the FAR maps above to see the land area covered by each FAR level.

How can I find out if my county is a frontier county?

There are several answers to this question depending on which definition you select or are required to use.

You can determine if your county meets the fewer than seven people per square mile definition of frontier by using the U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts. Start typing in your county's name, then select it from the list that appears. Scroll down to the Geography section near the bottom of the page and look for Population per square mile.

The Am I Rural? tool on our website can be used to help determine whether a specific location is considered rural based on various definitions of rural, including the FAR and RUCA definitions.

You can also download the Frontier and Remote (FAR) Area Codes data files from the USDA's Economic Research Service website. FAR codes classify the most rural geographic locations in the United States using 2010 U.S. Census.

What are some of the healthcare challenges in frontier areas?

Access to healthcare

Frontier areas face the same difficulties as other rural areas in maintaining their healthcare workforce, although those difficulties can be amplified. These thinly populated regions cannot easily compete with the wages and amenities offered to healthcare professionals by hospitals and clinics in metropolitan areas. Even communities that currently have adequate staffing are often one doctor or nurse away from a shortage. For more information, see the Rural Healthcare Workforce and Recruitment and Retention for Rural Health Facilities topic guides.

Many frontier counties do not have a hospital. In frontier counties that do have a hospital, that hospital may face higher costs per patient than non-frontier hospitals due to the lower volume of patients served. In addition, frontier counties without hospitals are often clustered together, compounding the distance residents must travel to reach a hospital.

Some areas must cope with seasonal variations in healthcare demand when the population surges with tourists, seasonal workers, or retirees. The limited health resources available in frontier areas, including volunteer health services and costly medical evacuation services, may be required to care for seasonal residents, further restricting the resources available for permanent residents. Impact of Seasonal Population Variations on Frontier Communities: Maintenance of the Healthcare Infrastructure, a 2006 report from the National Center for Frontier Communities, discusses these dynamics through 3 case studies.

Other barriers to accessing healthcare in frontier areas include limited or unavailable public transportation options for low-income households, the elderly, and people with disabilities. Seasonal travel barriers can occur due to obstructions such as snow, ice, and flooding. Some island residents and residents of roadless areas must rely on air or boat transport to healthcare and for emergency medical transport. These areas are particularly dependent on fair weather conditions.

Health Risk Factors

Rural communities are at higher risk for substance use, suicide, obesity, cigarette smoking, and death from unintentional injuries such as motor vehicle accidents. While many studies have identified health disparities for all rural communities, few have focused specifically on frontier and remote rural areas. According to a 2014 article in the Journal of Rural Mental Health, mental and behavioral health providers have recognized problems of substance abuse and domestic violence as significantly more prevalent in frontier areas.

Traffic fatalities are also more common for frontier residents due to poor infrastructure, such as narrower roads with bidirectional traffic. In addition, the increased time to receive emergency services and to reach a hospital capable of treating severe trauma in frontier areas contribute to the fatality rate of frontier residents.

The economy in frontier areas is often based on a few specific industries such as farming, ranching, tourism, logging, and mining. These industries, other than tourism, are associated with higher numbers of unintentional injuries, elevating the need for accessible healthcare, emergency medicine, and emergency medical transportation.

What health-related infrastructure challenges are unique to frontier areas?

The remoteness of frontier areas, which for many residents is a key appeal to living in such areas, can create risks and disadvantages related to accessing healthcare and to maintaining safe living conditions. Low population density creates challenges for an operational healthcare infrastructure, access to emergency care, and public health infrastructure. Counties and state agencies may lack the funding and/or staffing capacity to provide public health services in very remote areas. Our Rural Public Health Agencies topic guide presents general challenges to providing rural public health services, which are magnified in frontier areas.

As noted above, some frontier areas depend on air or water transportation to access the mainland for commercial and healthcare needs. Rural residents overall carry a burden of cost and time in order to access care, and that burden is often even greater for residents of frontier areas. Moreover, frontier areas may lack the resources to maintain safe roadways, which can often be extensive and exposed to harsh weather conditions that render them accessible only during certain seasons. The U.S. Department of Transportation's Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) offers a Manual for Selecting Safety Improvements on High Risk Rural Roads, which outlines improvements to make high-risk rural roads safer, noting challenges to applying treatments to high-risk rural roads. For more information on transportation challenges in rural areas, see the Transportation to Support Rural Healthcare topic guide.

Frontier areas also face challenges related to maintaining safe drinking water and waste management. This is particularly an issue for communities in the U.S-Mexico border region, as highlighted in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) report Border 2025: United States – Mexico Environmental Program. Water quality and waste management are also an issue for remote Alaska Native villages, as described in a 2020 EPA report on the Alaska Native Villages Grant Program, which offers program highlights of specific community challenges. For households that depend on both wells for drinking water and septic systems, contamination and pollution can be a significant problem to accessing potable water. Our Models and Innovations feature on the Portable Alternative Sanitation System (PASS) offers an example of a solution to water and wastewater challenges in a remote Alaska Native village.

As the COVID-19 pandemic has made clear, broadband access is a key issue for rural populations to access healthcare services and make full use of their health data. Areas with low population density are often the last priority for broadband expansion as serving frontier areas is less profitable for providers compared to more highly populated rural and metro areas. Satellite internet providers have long served remote consumers, but low speeds, potentially high costs, and intermittent service can be inadequate for many users to utilize video telehealth, online education, and other web-based activities. For more information on rural telehealth and broadband access, see the Telehealth and Health Information Technology in Rural Healthcare topic guide.

How does government ownership of large tracts of land affect the ability to provide services in frontier areas?

According to Caroline Ford, former Board President of the National Center for Frontier Communities (NCFC), “Counties and states that have a large presence of federal government ownership change the economic and health outlook of frontier communities.” Local tax dollars typically help support healthcare at the community level; however, frontier counties with lands owned by the federal government instead receive Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILT) for those lands. PILT is a Congressionally-mandated program that often does not provide sufficient resources to support the level of healthcare and human services the county would desire. In addition, local taxes in areas with national parks and other tourist destinations are impacted by seasonal employment and migration associated with tourism. Ms. Ford further states, “The seasonal nature of the economy significantly impacts the ability of these communities to collect and distribute tax revenue, or to maintain stable healthcare services dependent upon volume for quality and cost effective services.”

Are there funding or reimbursement advantages to being considered a frontier area?

Most of the programs that frontier areas can access for grants and enhanced reimbursement are available through shortage designations, including the Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) and Medically Underserved Area (MUA) designations, rather than through a designation as a frontier area. The Health Center Program gives special consideration to sparsely populated or frontier areas. However, frontier areas may find it difficult to obtain a HPSA score and often have lower scores compared to more populated areas due to the scoring rubric weighing heavily on the population to provider ratio and infant health index.

The Affordable Care Act, passed in 2010, included a clause that provides protections to hospitals and physicians in eligible frontier states by establishing a floor on the Medicare wage adjustment factor and practice expense index. Eligible states are defined as all states in which at least 50% of counties have an average population density of six people per square mile or fewer. Currently, states that meet these criteria are Alaska, Montana, Nevada, North Dakota, South Dakota and Wyoming.

Frontier communities are rural, and therefore qualify for many rural-specific health-related funding programs, such as the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy's Rural Health Care Services Outreach Grant Program and Rural Health Network Development Grant Program. For additional funding programs available to frontier and other rural areas, please see our Funding and Opportunities library.

What types of models have been developed to address frontier healthcare issues?

Frontier areas are diverse and dynamic, and providing healthcare to residents of these remote spaces is often challenging. The Critical Access Hospital (CAH) was one of the first innovations in provider type for rural areas, designed to preserve and sustain essential healthcare services.

A demonstration entitled Frontier Community Health Integration Project, or FCHIP, is a frontier-specific program that tested service delivery and reimbursement models that began in August 2016. This program implemented waivers of certain Medicare policies for CAHs in 3 specific areas: telehealth, nursing facility care, and ambulance services. The waivers were implemented at 10 CAHs in the frontier states of Nevada, North Dakota, and Montana. More information can be found at Frontier Community Health Integration Project Demonstration on the CMS.gov website, including a 2020 report on the model that covers the program's impacts. In 2021, FCHIP was extended for 5 additional years. Also, our Testing New Approaches section provides additional information about the Frontier Community Health Integration Program.

Many frontier areas, particularly in Alaska and remote frontier regions, do not have nearby hospitals. The Frontier Extended Stay Clinic (FESC) was a Medicare payment demonstration designed to show that enhanced reimbursement could spur the development of limited observation services (up to 48 hours) in frontier clinics, that such services could be delivered safely, and that they ultimately save payers money, primarily by avoiding costly transportation to a higher level of care. The 5 demonstration clinics were all isolated, fairly large, and sophisticated outpatient clinics: 4 Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and 1 Rural Health Clinic (RHC). All of the clinics successfully met the federal conditions of participation and demonstrated cost savings, patient safety, and patient satisfaction. However, the start-up cost was a significant factor, particularly in meeting the enhanced life-safety code requirements. A final report on the demonstration posted in 2014, Evaluation of the Medicare Frontier Extended Stay Clinic Demonstration: Report to Congress, provides key findings from the project:

- The costs of building and maintaining extended stay capacity are high.

- The demand for extended stay services among Medicare beneficiaries is low.

- Extended stay services improve beneficiaries' experiences.

- Extended stay services promote appropriate monitoring and observation services.

- Frontier communities would likely not be able to sustain extended stay capacity under fee-for-service Medicare.

More information on the model is available from Testing New Approaches: Frontier Extended Stay Clinics.

As of January 1, 2023, eligible rural hospitals can seek the Rural Emergency Hospital (REH) designation, established in response to rural hospital closures. The REH designation is designed to support critical outpatient hospital services in rural communities that might not have the capacity for a Critical Access Hospital. For more information on the designation, see our Rural Emergency Hospitals topic guide.

Telehealth may be one of the most important developments to positively address healthcare workforce issues in frontier areas. Patients in frontier areas can receive healthcare, including specialty care, more locally, reducing the need to travel long distances to receive healthcare services. With telehealth technology, primary healthcare providers can work with specialists to provide more specialized care. Telehealth has the potential to enhance the quality of care, improve health outcomes, and reduce healthcare costs in both rural and frontier areas. However, the availability of telehealth has not been consistent throughout these areas due largely to the lack of broadband availability. For additional information about telehealth, see Telehealth and Health Information Technology in Rural Healthcare.

What are some examples of workforce models that have been used to address healthcare issues in frontier areas?

Community Health Aides (CHAs)

The Community Health Aide Program (CHAP) was launched to provide healthcare in remote areas of Alaska through Community Health Aides (CHAs) under the supervision of a physician. In 2016, the Indian Health Service (IHS) formed the CHAP Tribal Advisory Group (CHAP TAG) to expand the program in the lower 48 states. CHAs work in more isolated locations and rely on telemedicine and other electronic means of communication with physicians to facilitate the care given to patients. CHAs work with a variety of patients and conditions that include mental health, trauma, and chronic disease. Some CHAs work as itinerants and travel to several communities to provide healthcare services.

Basic training for Community Health Aides can take 14 months or more and includes both classroom time and clinical practice. For more information about the Community Health Aide Program (CHAP), see the Health Aides of Alaska website.

Behavioral Health Aides (BHAs)

Several states have developed Behavioral Health Aide (BHA) models that provide a variety of behavioral health services depending on the needs of the community or the state. Models include BHAs working as care coordinators, health case managers, and community support workers. Some BHA programs may require a bachelor's degree or an associate degree while other programs may require a high school diploma. How Alaska Supports Rural and Frontier Behavioral Health Services provides a model of a successful program implemented within the Alaska Tribal Health System, including information on BHA training and certification and other aspects of program administration. For additional information, see Strategies for the Delivery of Behavioral Health Crisis Services in Rural and Frontier Areas of the U.S.

Community Health Workers

Community health workers (CHWs) provide individualized and culturally competent health services in rural and frontier areas. Acting as a liaison between the provider and the consumer, CHWs assist the patient to navigate the healthcare system, provide care coordination, offer translation services, and make referrals for health and social services. Specially-trained CHWs may offer enhanced traditional healthcare delivery. For example, the Health-able Communities Program, developed by a consortium of 9 healthcare facilities in Idaho, addresses the region's specific medical needs by pooling different components of well-known CHW models to create a hybrid CHW role. Trained CHWs, overseen by physicians and nurses, provide cancer and chronic disease screening, health and wellness education, chronic disease self-management classes, and assist with medication delivery in remote areas. See Community Health Workers in Rural Settings for additional information.

Community Paramedics (CPs)

The emergence of community paramedics (CP) is an evolving healthcare model allowing paramedics to expand their roles by assisting with primary healthcare and preventive services, having the potential to improve the health and well-being of frontier populations. CP services can vary widely depending on the needs of the community, and may include geriatric disease management, medication management and compliance, home visits, palliative care, wound care, and vaccination. Frontier and Remote Paramedicine Practitioner Models discusses several paramedic service delivery models in the U.S. and other English-speaking countries that have the potential to support and improve health and well-being of frontier populations. See the Community Paramedicine topic guide for more information.

Dental Therapists (DTs) and Dental Health Aide Therapists (DHATs)

Several states have authorized the licensure of Dental Therapists (DTs) or Dental Health Aide Therapists (DHATs). These midlevel providers work under the supervision of a dentist and may provide education, dental therapy, and dental hygiene services. The Alaska Dental Therapy Aide Program (ADTEP), a two-year educational program focused on prevention strategies and culturally competent dental care, has seen long-term success in promoting access to care in rural Alaska Native communities. According to a 2018 study, DHAT treatment was associated with increased preventive care utilization and fewer tooth extractions in Alaska's Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. For additional information on DTs and DHATs in rural and frontier communities, see our Oral Health in Rural Communities topic guide.

Recruitment and Retention Strategies

Various types of recruitment and retention strategies have been used to address the significant shortages of health professionals often found in frontier areas. For example, the FORWARD NM: New Mexico's Pathways to Health Careers workforce program seeks to improve the supply and distribution of healthcare professionals through community and academic educational partnerships that include school-based health career clubs, MCAT preparation, and rural clinical internships and rotations.