Nov 06, 2024

The Making of a Physician: Pipeline Dwell Time, Knowledge Assessments, and Path to Licensure

When individuals head into the physician workforce pipeline, the desire to "go rural" is often not a choice kept — or even a feasible choice — because, along the way, the choice is influenced by social factors and real-world experiences. Examining a physician's path from college to final independent licensure might bring understanding to why any physician's practice site choice changes with time.

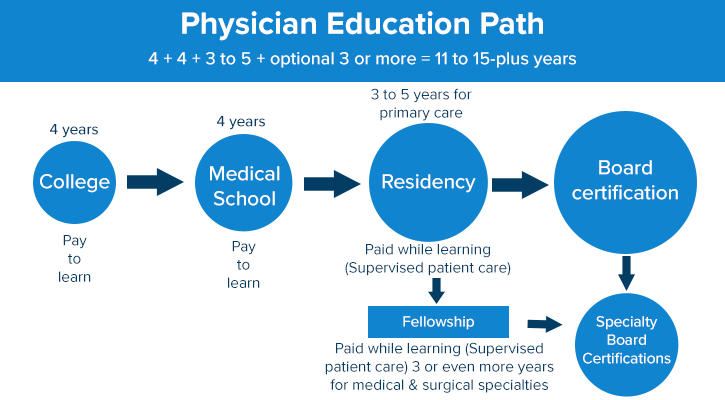

To start, most individuals enter the pipeline in late adolescence, often at age 18, and emerge as an adult around age 28 or older. The first eight years — a pay-to-learn-to-be-a-doctor timeframe — usually starts with a four-year college degree, followed by four years in either an allopathic (MD) or osteopathic (DO) medical school.

Next come the post-medical school years, referred to as the graduate medical education (GME) years, when newly graduated physicians enter the paid-to-learn environment of residencies. Residency offers those with new MD degrees something akin to the apprenticeship training used by other professions. New doctors spend their days — and their nights — increasing their knowledge and skills by providing patient care while under expert supervision of senior physicians.

Resident salaries are mostly funded by Medicare and Medicaid, with some support coming from private insurance, host program monies, or other sources. As skills advance with their years in training, residents' pay increases with each year in residency. Although multiple and regional variables influence a resident's wage — officially considered a stipend — a recent survey indicated that in 2023 an average salary for residents in their third year of training might be around $70,000.

Setting Standards: Medical Education Oversight Organizations

While medical school standards are linked to two independent organizations, the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the American Association of the Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine (AACOM), quality oversight of all residency education programs is provided by another independent organization, the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).

Training duration is also strategically linked to practice type. For example, the primary care specialty fields of family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics are three-year residencies; psychiatry and obstetrics and gynecology, usually four years; general surgery, a five-year residency. Tallying those years: From college start to residency completion, it takes doctors 11 or 12 years to gain the knowledge and skills of their chosen field.

However, in the U.S., doctors choosing a non-primary care specialty outnumber those choosing primary care. For the former, the pipeline dwell time now increases by a factor linked to a fellowship training, another paid-to-learn GME environment. Like residencies, fellowships are overseen by the ACGME and come with federal salary funding.

One example of fellowship and advanced fellowship training is seen in cardiology. After completing a three-year residency in internal medicine, the specialty that provides the primary care of adults, some individuals choose general cardiology. General cardiology concentrates on all the physical matters of the heart and involves three more years in supervised fellowship training. However, if a cardiologist wants to focus on procedures like cardiac catheterization — a procedure that involves measuring heart pressures and guiding tubes through a patient's heart blood vessels in order to identify problems like blocked arteries that cause heart attacks — another year of training occurs in an interventional cardiology fellowship.

Total years to learn to do cardiac catheterizations? Twelve. Age? If a traditional path is followed, training is completed around age 30.

Knowledge Assessment and Personal Disclosure: the Path to Independent Practice

Medical educators shared that it's also important to note that formal periodic knowledge assessments happen during a physician's trip through the pipeline — at a cost to the test taker.

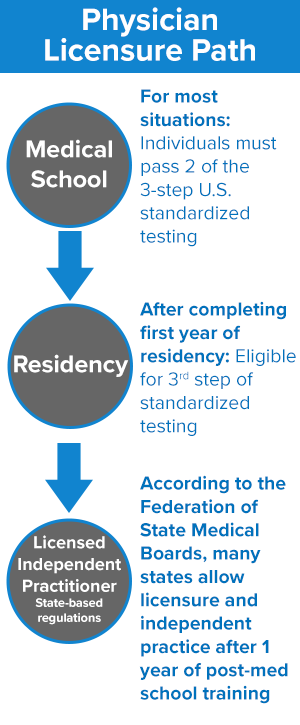

According to the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB), the first two steps of this licensing examination are taken prior to graduation from medical school. The final step of the examination sequence is usually taken in the first or second year of residency training.

After a residency comes the milestone of "being boarded," a label that comes by passing another fee-based knowledge assessment and overseen by one of three organizations: American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS), the American Board of Physician Specialties (ABPS), or the American Osteopathic Association (AOA). Each organization has its internal specialty and fellowship assessments and board eligibility (BE) criteria. Passing these exams is referred to as board certification (BC). Again, testing helps assure that the physician workforce is clinically competent and meets the practice standards established by peers in that specialty.

As is the routine for many professions, after initial certification comes periodic recertification, and those same organizations oversee those assessments, also fee-based.

Yet, There's More: Steps to State Licensure

No matter how prestigious the residency program or how high the specialty board scores, the legal privilege to provide unsupervised patient care comes only with a medical license granted at the state level.

State licensure, too, starts with a separate 3-step assessment geared to measuring the basic knowledge expected to be mastered by all physicians. Every state requires that a physician intending to practice in that state is individually reviewed according to the state's rules before being granted a license to practice medicine in that state. During this state-level process, the FSMB indicates that to be granted a medical license, most states require five items: proof of medical school graduation; passing scores on the 3-step sequential licensure exam; participation in one or two years of clinical residency; a statement of physical and brain health; and disclosure of any previous and current legal issues, such as malpractice cases or violation of any public laws. The final licensure approval is granted by the committee designated according to the policies of a state's medical board.