Nov 06, 2024

Growing the Rural Physician Workforce: Decades of Federal Funding Impacts Rural Graduate Medical Education

Related Article

The Making of

a Physician: Pipeline Dwell Time, Knowledge Assessments,

and Path to Licensure

In October 2023, the Bureau of Healthcare Workforce (BHW) released its physician workforce projections, noting that by 2036, metro areas will see a 6% shortage of physicians. In contrast, rural America is anticipating a 56% shortage.

For nearly 115 years, physician supply predictions have alternated between either "too few" or "too many" — except in rural America, where predictions have always been "too few."

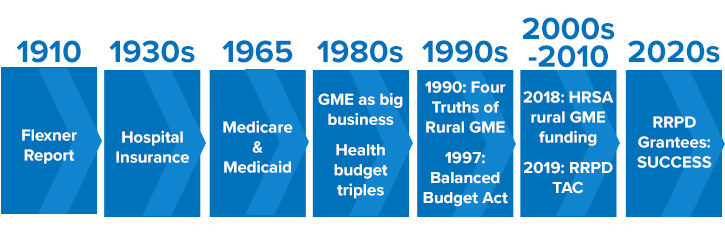

Workforce experts pointed to events along a timeline of over 100 years that have challenged creating an adequate rural physician workforce. However, over the past 25 years, initial slow gains are now accelerating as a result of new federal funding. A timeline review shows these gains are linked to the tenacity of federal agency representatives and accrediting bodies who've been orchestrating system changes. Bolstering the efforts of rural physician educators and healthcare systems, these changes are anticipated to impact the BHW's shortage prediction for rural America.

First: The Language and Length of Physician Training

Understanding physician supply starts with understanding the unique language and processes linked to a physician's training path. In contrast to other professionals whose "graduate education" starts after their college degree, physicians' college and medical school education is referred to as undergraduate medical education (UME) while graduate medical education (GME) refers to the training after medical school and completed in programs called residencies and fellowships. In The Making of a Physician: Pipeline Dwell Time, Knowledge Assessments, and Path to Licensure, follow the timeline and processes leading to the independent practice of medicine.

Place-Based Training: Philanthropy's Early (Negative) Impact

"In the case of stranded small groups in an unpromising

environment the thing works out differently. A century of

reckless over-production of cheap doctors has resulted in

general overcrowding; but it has not forced doctors into

these hopeless spots."

— Abraham Flexner

The first major timeline tick mark comes in 1910 with the landmark "Flexner Report." In the early 1900s, philanthropic organizations expressed concerns around the quality of the nation's healthcare despite an excess number of physicians. Commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, Abraham Flexner, an expert in education — but not medicine — discovered that physician oversupply existed because of the education model of the time: medical education as a for-profit enterprise. Any individual could provide patient care if they were able to pay the fee for an education labeled "medical." No filters were in place for either candidate selection or education quality.

The report impacted rural physician training when it triggered closure of nearly half of the nation's medical schools, including rural place-based medical education sites of the highest quality. Further rural impact was noted many years later in a 1988 report to Congress when rural workforce experts suggested that it would take nearly 100 years to overcome the report's negative influence on place-based education, still recognized as a critical evidence-based approach for training the rural physician.

But, Fifty Years Later: New Health Policy with an Intentional Broad Reach to Include Rural

Fifty years after the Flexner Report, a 1965 healthcare policy promised impact on rural physician supply. But before examining that policy, there's a related backstory linked to hospital insurance.

Prior to the 1930s, life and casualty insurance were sold because "life" and "casualty" were definable and measurable. In contrast, "health" was considered uninsurable because it was neither. However, because hospital stays were both, the 1930s saw new commercial hospital insurance products emerge that were both popular with the public and profitable for insurance companies — and eventually offered by employers in the '40s and '50s to attract workers.

Fast-forward three decades into the 1960s, when historians noted the nation's health policies began to link with the country's increasing social awareness. Because health insurance had become so popular with the nation's workforce, this insurance was replicated by the passage of the Social Security Amendments of 1965, or Public Law 89-79 (P.L. 89-79) to support the aging population and those experiencing poverty. This landmark policy created two government health insurance programs: Medicare, a health insurance program for the elderly, and Medicaid, a health insurance program for people with limited income.

Public records noted that this comprehensive legislation triggered more Congressional considerations. For example, in order to provide good care for these millions of new federal beneficiaries, were there enough hospital beds? Were there sufficient numbers of the best physicians to provide care? These questions around preparedness led to P.L. 89-79's landmark amendment language linking government support for GME:

"Many hospitals engage in substantial educational activities, including the training of medical students, internship and residency programs, the training of nurses, and the training of various paramedical personnel. Educational activities enhance the quality of care in an institution, and it is intended, until the community undertakes to bear such education costs in some other way, that a part of the net cost of such activities (including stipends of trainees as well as compensation of teachers and other costs) should be considered as an element in the cost of patient care, to be borne to an appropriate extent by the hospital insurance program."

The rural impact of this legislation?

An implied expectation: Those who were paid to train physicians were to also attend to the nuances around the appropriate geographic distribution of these trainees. With financial support from taxpayer-supported GME funding through the Medicare and Medicaid programs, the hope was for physicians to be trained in enough numbers to provide care for all federally insured beneficiaries, including those living in underserved and rural areas of America.

The Next Twenty Years: Urban Hospitals and the Business of GME

With GME support through the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) — now known as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) — experts said the next two decades saw GME costs grow with little restriction and going mostly to urban hospitals. In fact, by the mid-to-late 1980s, experts said GME had become "big business" for urban hospitals.

Why urban and not rural areas? Because the country's existing GME infrastructure was mostly in urban hospitals. This allowed them to both start new programs and expand already existing programs with the new GME support. Additionally, any costs not covered seemed to be easily absorbed by large urban institutions.

As federal reimbursement became a positive line item for urban GME sites, experts pointed out that the original GME language — "it is intended, until the community undertakes to bear such education costs in some other way" — hadn't been forgotten. However, by the 1980s, GME payment machinery had scaled to the point that the robust "community" leadership and financial incentives needed to move GME away from its federal support were unlikely to materialize.

By the 1980s, then, GME experts became fully aware of another issue impacting final rural practice site choices: Urban place-based training — with its own needs for retaining trainees of its residencies and fellowships to meet urban's own future physician workforce needs — was overshadowing the implied expectation of appropriate geographic distribution of physician trainees.

Rural stakeholders realized the urgent need for new approaches.

One mid-1980s solution capitalizing on place-based training evidence was the "rural training track" (RTT), which offered residents first-year training in an urban hospital and the last two years in rural settings. This arrangement bypassed much of the costly GME infrastructure and provided the large patient care volumes required for training program accreditation. In 1986, the first RTT in Colville, Washington, saw immediate physician retention success. Later, RTT success was replicated in four more states.

However, despite these successes, forward motion seemed to halt when rural healthcare leaders found themselves dealing with another major timeline event with impact on rural GME: the 1980s healthcare budget crisis and the large number of rural hospital closures.

The 1980s: Budget Crisis's Rural Impact

In the 1980s, federal healthcare spending was exploding. An emergency budgetary brake was pulled by creating a reimbursement mechanism intended to realize cost savings by incentivizing more efficient clinical practices. Its name: the Prospective Payment System (PPS).

With PPS implementation, a large percentage of hospitals with fewer than 100 beds closed. Of those, rural hospitals comprised about half. Although closures were the main concern, the rural GME impact was obvious: Due to the unintended consequences of PPS, if rural hospitals weren't surviving, how could new RTT programs find hospital host sites?

As this closure crisis was sorted, something positive came from the negative impact with implications for rural GME: a new office within the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) solely dedicated to the nation's rural health. With Congress recognizing the need for increased scrutiny of healthcare policy impact on rural America, the statutory language of P.L. 100-203 included the creation of the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP). One of its two initial charges inherently linked to rural GME was the recruitment and retention of rural physicians.

The 1990s: Untangling the Rural Elements of Federal GME Policy

Moving on to the events in the 1990s impacting rural GME, cue first the voice of Keith Mueller, PhD, the director of the Rural Policy Research Institute (RUPRI) and its Center for Rural Health Policy Analysis.

"When I was National Rural Health Association president in 1996, we were still in the throes of recovering from the damage done by the shift to prospective payment causing rural hospital closures," he said. "Rural physician supply issues were still present and, actually, those supply issues were always a constant buzz with crescendo variation depending on what was going on in the political environment. I remember the issues at that time were tied to the same old policy argument, just this time connected to GME: Regardless of what the original intent was, often federal programs ended up serving the financial needs of tertiary care hospitals with a strong bias toward hospitals with lots of specialists — and a lot of GME dollars were flowing to the Northeast."

1990: Four Truths of Rural Practice Site Choice

- Students from rural areas are more likely than those from urban areas to train in primary care and to return to rural areas to practice.

- Residents who have a significant part of their residency training in rural areas are likelier to choose to practice medicine in rural areas.

- Family medicine is the key to rural health.

- Residents practice close to where they train.

Source: Talley RC. Graduate medical education and rural health care. Acad Med. 1990.

Mueller also pointed out that new health policies in the late 1990s added further complexity to rural GME when P.L 105-33, the 1997 Balanced Budget Act (BBA), was passed. With the BBA designed to save around $100 billion linked to its Medicare, Medicaid, and other health-related changes, it also reacted to a physician oversupply prediction by capping residency growth to physician trainee numbers as of December 1996.

However, recall this: Rural America has never been challenged with an oversupply of physicians.

For rural GME, these caps seemed yet another unintended policy consequence, especially considering the policy's counting methods. The process excluded family medicine physician trainees working in rural sites away from their urban programs, resulting in about a 30% undercount of baseline numbers. For urban centers with rural training sites, then, the big BBA picture was that their programs had just undergone a significant size decrease. However, rural stakeholders reported that it felt different, likened to a cut of almost all slots for trainees who might consider a future rural practice site.

Experts said, however, it's imperative to recognize that the intent of the new public policy was not to cut rural training positions. Noting an "outpouring of concern," a 2000 report from the Council on Graduate Medical Education (COGME) pointed to Congressional efforts to "refine and 'correct' the law." Experts close to those efforts indicated that these changes were actually the result of a sole member of the Senate Finance Committee: North Dakota Senator Kent Conrad.

Recorded in the committee's final report, Conrad's comments allowed CMS to support the BBA's intent with regard to rural GME in its resulting regulations. Without his influential language, these experts emphasized, new rural GME sites would have been impossible. Additionally — with the Senator's comments having helped craft the BBA's final rule — two years later the way was paved for even more rural GME changes in the language of the 1999 P.L. 106-113 the Balanced Budget Refinement Act (BBRA).

Balanced Budget Refinement Act (BBRA) GME Rural Provisions

- Permit rural hospitals to increase resident limits by 30%

- Allow GME payments for non-rural facilities operating accredited rural training programs in rural areas

- Permit reclassification as rural hospitals if:

- Located in a rural census tract of a metropolitan statistical area

- Located in a state-designated rural area

- Meeting other criteria specified by the Secretary

Source: 2000 Council of Graduate Medical Education report: The Effects of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 on Graduate Medical Education

By August 2000, CMS released new regulations providing further clarity around rural GME: Hospitals adding rural training tracks could incrementally increase their resident numbers with totals to be capped after five years. Along with these cap regulations, the final rule also focused on rural definitions and program typology.

To summarize the 1990s?

In addition to Senator Conrad's contribution, experts said there were many coordinated activities across federal agencies that helped bring the BBRA regulations further into line with the BBA's "intent of encouraging physician training and practice in rural areas." If not for that BBA final rule language, these experts emphasized, the only rural residencies in place today would be the few that existed prior to 1997 or those that had funding from non-federal sources.

However, despite the final rule's favorable language, over the next several decades there was little growth in rural GME programs, and records from the next decade uncovered "why."

2000s-2010s: Rural GME Momentum Builds

Why was change in rural GME so slow in the years following the BBA and BBRA?

Insight into the slow forward motion also comes from exploring the themes of requests Congress was making of its investigative and research arms, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and the Congressional Research Service (CRS). For example, in 2009, one request was geared to medical training trends, medical student debt, and physician specialty selection with categories of primary care, and the higher-salaried surgical and procedural specialties — of course of interest to low-resource rural America. Next came requests for details around CMS's GME-specific spending with another report touching on geographic maldistribution: In 2015, of the nation's total 127,000-plus physician trainees, only 1%, totaling 1,223 trainees, were in rural areas.

These reports restated the question: Why were these rural trainee numbers still so low? Why were the rural GME funding options — hard-won in the final rulemaking process to make good on the intent of the BBA and BBRA nearly 20 years before — of such infrequent use?

Looking for answers, GAO authors "reviewed relevant agency documentation and interviewed CMS officials and other officials," including those who'd worked with a 2010-2015 HRSA-funded rural GME technical assistance program. Of the numerous rural challenges, this project found that for so many rural GME-eligible hospitals, the high start-up cost of training programs was insurmountable in light of their increasing financial vulnerability. Simply stated, after final rules are published, stakeholders with resources are usually poised for immediate action. However, for those with fewer resources — like rural healthcare systems — this is not so much the case.

Yet, along with uncovering the cost barriers to rural training site start-up, new research emerged with data about exactly why new rural programs should be started: retention of rural trainees. Linked to the earlier work of the technical assistance program, a 2016 brief reported that the 2008-2015 RTT rural placement rates were more than 35% and noted to be twice the proportion of all allopathic family medicine physicians.

Additionally, new advocacy approaches for rural training were used. Pivoting away from dependence on urban medical schools for promotion, rural GME experts engaged other rural stakeholders — like the State Offices of Rural Health (SORHs), Area Health Education Centers (AHECs), and organizations like the National Rural Health Association, which had officially formed a rural medical educators group — to elevate rural residency training.

But rural stakeholders also realized that favorable reports and a few positive results alone weren't going to be enough to generate the course correction needed to overcome more than 100 years of physician maldistribution. More and more, it became apparent that rural GME was going to need specialized federal funding for GME start-up.

By 2018, Congressional support for further rural GME came through in the 2018 appropriations bill with its funding for the establishment of a rural residency planning and development technical assistance center. Again, experts close to the efforts pointed out that the Rural Residency Planning and Development (RRPD) program leveraged lessons learned from the 2010-2015 technical assistance program's results — and was expressly created not only to leverage prior BBA and BBRA gains in CMS's flexibility for new rural GME, but to support programs in states allowing Medicaid GME support.

Additionally, this funding would go directly to rural healthcare facilities to support the start-up costs of new rural GME residencies starting in 2019. Technical assistance would also be funded to help the facilities navigate the many linked complexities.

A New Era? Federally Funded GME Programs Meet the Needs of Rural Communities

Now almost midway into this current decade and with six cohorts totaling 84 grantees, the success of the new RRPD program funding can be seen from rural coast to rural coast.

Emily Hawes, PharmD, deputy director of the University of North Carolina-based RRPD technical assistance center (TAC), emphasized the effectiveness of the previous efforts by others to expand GME.

"It's important to acknowledge that the success of our RRPD cohorts is due to previous decades of work by many rural stakeholders, GME educators, and Congressional and federal agency representatives," she said. "It was their collaboration, their tenacity, their research, and the stories of these pioneers in rural place-based education that allowed this program to make the needed difference for our rural physician workforce."

Mark Holmes, PhD, is the TAC's research director and director of UNC Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research. He added further perspective on the impact of this new federal funding.

"Especially in recent years, there's been a clear commitment to creating policies that support the goal of rural GME," he said. "Congress began paying more attention to existing policy barriers that hadn't been addressed. That attention, combined with the successes of the RRPD grantees, has spurred activity throughout government with Congress and the executive agencies showing a willingness to pursue the goal."

In 2021, More Positive Policy Impact on Rural GME

Rural GME experts said that the 2021 Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA) and its resulting regulations impacted rural GME in several key ways. For example, it allows for expansion of rural training linked to existing urban programs without the burden of separate program accreditation. It also provides a reset option for rural hospitals' caps linked to long-ago resident rotations and provides positive changes connected to other technical elements linked to GME reimbursement.

But along with these supports — and in addition to the fact that these new and expanded programs bring an immediate increase in physician access to their rural communities — Hawes pointed out that to recognize the CAA's full impact is to recognize that it's linked to its own timeline.

"It will take years for the CAA's positive impact to be fully realized because it takes years to start new programs and years to train physicians," she said.

Hawes and Holmes said that part of their TAC work includes clarifying for policymakers, rural healthcare organizations, and other GME stakeholders that RRPD eligibility can translate into rural success.

"Although rural programs might seem a stark contrast to large urban programs where resident training usually occurs in the same institutional building for numerous consecutive years, our grantees' track record proves that not only can rural health facilities host residency programs, they can successfully fill those programs," Hawes said, adding that one result of new programs is bringing immediate increased physician access to host communities.

Both TAC leaders emphasized the effectiveness of the grant's financial start-up support. With some research showing estimates of over $1 million attached to the one-time start-up costs for new GME programs — Note: regardless of program size, these rural start-up costs aren't less because programs are smaller — the RRPD funding is proving game-changing for eligible rural health facilities that otherwise couldn't manage start-up costs.

According to Hawes, of the country's rural GME programs currently existing, 20% have been funded by RRPD.

Hawes and Holmes also emphasized that it's just not start-up cost support that's getting new programs up and running — it's the collaborative, "turf-free" work of many. Hawes estimated that, in some way, about 30 collaborating organizations assist new programs with the mechanics of start-up, including program needs around financing, academic accreditation, marketing, legal requirements, and much more.

Zooming in on Small "N": the Power of Rural GME's Small Numbers

Acknowledging those concerned with the small scale of rural as compared to urban GME, experts said that small numbers have significance in rural America:

- 2015: Only 1% of GME training was represented by rural trainees but by 2019-2020 had increased to 2%, a substantial gain in only 5 years

- 2016: Research shows that 35% of family medicine RTT graduates practiced in rural areas.

- 2022: From a southern state's rural GME: of 16 graduates in practice for at least three years, 9 are still in rural practice sites

Yes, small numbers: 1%, 2%, 35%, and 9. However, some experts point out that, in rural America, small can make an enormous impact. For example, 100 or 200 physicians can profoundly impact the predicted number of 700 more primary care physicians — or the 1,200 more needed specialty care physicians — currently estimated for rural America to reach the established standards for delivering a "national average" level of care.

Sociologist and associate professor Davis Patterson, PhD, former director of the WWAMI Rural Health Research Center, commented on the significance of small numbers, gained from the perspective of his extensive workforce data analysis experience.

"In workforce research, it's a critical point that many don't consider when we talk in large numbers and shortages of thousands," Patterson said. "One physician in an urban underserved area is important, but one physician in a rural area makes a difference for people and communities in a vast geographic area."

As lead author of a recent landmark paper on rural GME program retention data, Patterson pointed out that these small numbers in rural GME have impact outside of just immediate increases in a rural community's healthcare access.

Rural GME Funding's Reality: Meeting Rural Needs

Hawes pointed out that new rural residencies are not built on a one-size-fits-all template. Instead, she said, these programs are being designed to meet the needs of the rural communities that host them.

"With persistence and innovation, these RRPD grant recipients are designing programs that are meeting their rural service area's challenges," she said. "Additionally, in even a wider effort, they are also successfully incorporating their communities' assets."

Despite this new rural GME growth, experts said there are still limiting policy challenges. Recent analyses articulated that the outcomes of public laws like P.L. 116—260, the 2021 Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA), were to increase rural GME slots, but anticipated results are tempered by other laws allowing for "changes in rural hospital reclassification initiated by a series of lawsuits and court decisions," as outlined in a December 2022 report. Additional concerns, articulated in early and late 2023 reports, found that many of the new CMS-approved GME slots were awarded to urban programs.

Holmes weighed in on these policy issues.

"It's easy to see why rural constituencies benefit from these investments in rural training," he said. "But this is also an issue where urban systems are supportive as well. As urban systems become more engaged in rural communities, they increasingly have a stake in ensuring that there are strong training opportunities in rural settings."

With a forecasted seventh funding cycle for the RRPD, Hawes and Holmes shared that these additional funding cycles can address what they've now noted as "pent-up demand" for new rural GME programs.

Hawes explained how this can also support current grantees to expand their rural training offerings.

"We're seeing that if an organization successfully started a family medicine program, they realize the power of their infrastructure and capability," she said. "They become confident that they can meet other community needs, like starting a psychiatry program — and nothing beats seeing rural GME success begetting more rural GME success."