Aug 28, 2024

Rural Louisiana Programs Create Healthier Schools

by Allee Mead

The Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP) Delta States Rural Development Network Grant Program supports healthcare networks in Alabama, Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Tennessee as they work to address issues such as diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease.

Two grantees in Louisiana are working to improve children's health in the school setting. The Adolescent Pre-Diabetes Prevention Program screens high school students for prediabetes and then provides Healthy Lifestyle lessons to reduce their risk, while the EatMoveGrow program collaborates with elementary schools to improve their health environment by increasing nutrition and physical activity opportunities for students.

Creating the programs

Patrick Cowart, Project Director of the Adolescent Pre-Diabetes Prevention Program, said that when he and his team first proposed this program, they modeled it off the Richland Parish Hospital's Promising Practice Model, a program designed to reduce prediabetes in adults. "There was no other prediabetes program for adolescents anywhere in the country," he said.

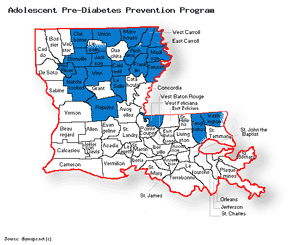

The program serves 21 parishes, most of them in north Louisiana and a couple located in the boot of the state bordering Mississippi. Ninth graders at 39 high schools are recruited to be participants in the program throughout their high school career. Students' parents sign consent forms for students to participate in the program, and then the students are screened. Cowart said program coordinators are working on recruiting eighth graders to enroll before they start high school.

Screening events are divided into different stations. Students sign in; have their height, weight, and blood pressure measured; and fill out a questionnaire. Then they have a counseling session with a coordinator who discusses body mass index (BMI) and draws blood to measure A1C levels. These screenings determine which students are eligible to participate in the program. When students check out of the screening event, they receive a T-shirt and other gifts. Depending on a student's BMI, a student might also visit a station to learn more about factors contributing to a high BMI.

Students only complete blood draws if their BMI and other contributing factors are high, if they or their parents request one, or if a school nurse refers a student to have blood drawn. The Richland Parish Hospital (also called Delhi Hospital) processes the blood samples for free.

About 50% of the students who complete the screening are enrolled in the Adolescent Pre-Diabetes Prevention Program. This year, about 1,100 students were screened, of whom 550 were enrolled in the program. Program enrollees are screened every 90 days to track their height, weight, blood pressure, and A1C.

In addition, program enrollees receive three Healthy Lifestyle lessons each semester. Each lesson has a nutrition and exercise component and covers other topics like setting goals. The lessons also include a recipe. "The recipes are all good," Cowart said. "We tried them all, and they're worth eating. We do them at my house every once in a while."

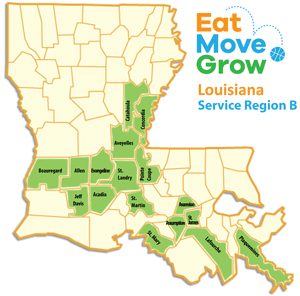

EatMoveGrow (EMG) is a comprehensive obesity prevention program serving over 15,000 elementary students across 17 rural parishes. Originating as a small dental initiative in a single elementary school, EMG has expanded to encompass nutrition education, physical activity programs, playground interventions, and wellness initiatives.

EatMoveGrow operates through School Wellness Committees (SWCs) established in participating schools. With the support of EMG health educators, the SWCs complete the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) School Health Index to identify their health needs. These committees then develop and implement monthly nutritional and physical activity programs targeting first through third grade students.

Nutrition education within EMG focuses on promoting healthy eating habits, including increased fruit and vegetable consumption, reduced sugar intake, and mindful snacking. EMG also works with the Louisiana State University (LSU) AgCenter for the Harvest of the Month program and support for school garden initiatives. Additional components of the EMG program address social-emotional learning and oral health.

The Health Enrichment Network (THEN) Executive Director Donna Newton and Project Director Amy Karam work with a team of six health educators to teach this nutrition and physical activity program and provide technical assistance, resources, and funding to 50 schools.

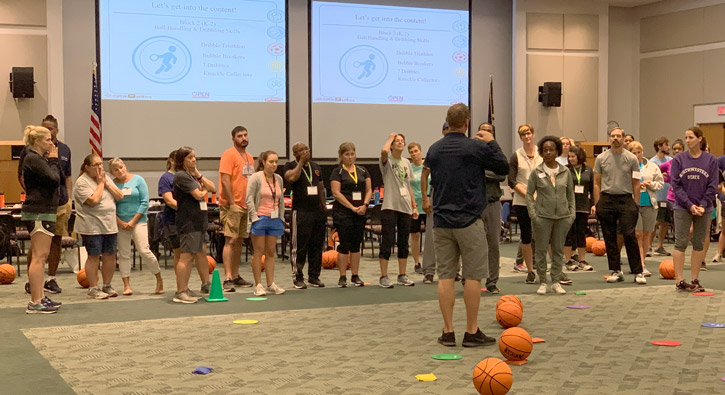

Newton and Karam reported that over 66% of EMG schools do not have certified physical education teachers, and many schools provide inconsistent or inadequate time or have limited equipment for physical education. EMG provides training in physical education for these schools.

These trainings equip teachers and volunteers with the necessary skills to deliver engaging physical activity programs. The EMG curriculum emphasizes incorporating movement into classroom instruction through "activity snacks" and creating active play environments on school playgrounds.

Creating positive changes

Cowart said that about half of the students enrolled in the Adolescent Pre-Diabetes Prevention Program make progress by losing or maintaining weight or lowering their BMI, blood pressure, or A1C. He added that he's seen students lose 80 pounds over the course of the program, which he said is an especially great achievement given that many students in the service area struggle to access or afford healthy foods.

Cowart has heard from coordinators about students who did not seem to pay attention during the Healthy Lifestyle lessons but later were able to repeat things they had learned from the program. Every year, students complete a pre- and post-questionnaire. One question asks students if they feel this program has been beneficial, and 90% of them say yes.

We've had kids, anecdotally, tell the coordinators, 'If y'all hadn't done this, I don't know what would've happened to me.'

Coordinators also report students and their families approaching them in grocery stores and other public spaces to share the progress they've made. "We've had kids, anecdotally, tell the coordinators, 'If y'all hadn't done this, I don't know what would've happened to me,'" Cowart said. He remembered one student who wanted to join the National Guard but did not meet medical requirements. After participation in the program, he was able to lose weight and meet the guidelines to join.

Cowart said that the program currently has a memorandum of understanding with Southwestern Oklahoma State University College of Pharmacy Rural Health Center, which is looking to replicate this work in Oklahoma. Coordinators have also given presentations about this program at the National Rural Health Association conference and Southern Obesity Summit. In 2018, the Louisiana Rural Health Association recognized this program as the Rural Health Program of the Year.

In the EatMoveGrow program, EMG staff in 2023 traveled over 27,000 miles, conducting 1,280 classroom visits and providing 544 hours of technical assistance to school personnel. To support program implementation, EMG has awarded 125 grants totaling $80,000 and leveraged an additional $300,000 in external funding in the last two years.

Newton and Karam also reported that EMG has demonstrated effectiveness and has been replicated by other programs. EMG is also aligned with CDC's Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) model.

Despite significant health challenges, our program has made a measurable difference in combating childhood obesity.

"By working hand-in-hand with local partners, we're creating healthier futures for our children," Newton shared. Karam noted, "Despite significant health challenges, our program has made a measurable difference in combating childhood obesity."

BMI measurement among 953 third grade students revealed a decrease in overweight and obesity rates from 38% in 2015 to 35% in 2018. Additionally, students showed significant improvements in health knowledge. In collaboration with the Pennington Biomedical Research Center, EMG is conducting further research to assess the program's impact. Studies include heart rate monitoring for physical activity levels and pre- and post-tests for knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. An upcoming study will measure fruit and vegetable consumption.

Networking and partnering

The Adolescent Pre-Diabetes Prevention Program partners with 11 school-based health centers (SBHCs). Cowart said that, at the beginning, there was some hesitation from school nurses, who might have been concerned that the program would take away from their work. But now, he said, he hears from school nurses who are "clamoring to participate in our program." In addition, working with SBHCs can be a great way to learn what will work with a particular group of students and what won't work.

The program hosts a consortium meeting twice a year at a retreat center. Principals and other school and SBHC employees listen to different speakers, participate in breakout sessions, complete fun activities like zip lining, and network with other schools. "We have principals in school districts that were one parish apart or next door to each other who didn't even know who those folks were," Cowart said. In addition, the networking allows the SBHCs opportunities to work together to continue students' care if they transfer from one school to another.

Cowart recalled a consortium meeting years ago where a principal from a low-income parish learned about SBHCs. Within months of that meeting, she had established an SBHC in her school, partnering with the local Federally Qualified Health Center.

Similar to Cowart's program, EatMoveGrow hosts an annual Teacher Summit. This gathering provides teachers and administrators with professional development, networking opportunities, and technical support. The summit has also fostered the creation of a support network among physical education teachers in the region.

Teachers who might think their schools are too small to implement certain projects or lack the experience to write grants gain confidence and ideas by seeing the successes of their peers.

"Teachers who might think their schools are too small to implement certain projects or lack the experience to write grants gain confidence and ideas by seeing the successes of their peers," Newton said.

Expanding its impact beyond the classroom, EMG has introduced two new social services programs this grant period in partnership with the Louisiana Rural Health Association. The first initiative pairs elementary schools with community health workers (CHWs) to connect students and families with resources such as housing assistance, transportation, employment support, and food security. The second program formalizes partnerships between schools and Rural Health Clinics, providing at-risk students with access to health education, preventive care, and clinical support.

"We're working hard to make sure kids have what they need, both inside and outside the classroom," Karam said.

Making manageable changes

Newton shared that EatMoveGrow delivers "resources directly to schools rather than requiring them to develop in-house solutions." This can help program coordinators gain buy-in by offering solutions instead of just identifying problems for schools and asking them to create something from scratch. At the same time, working one-on-one with schools and having each school create a School Wellness Committee helps make sure that the solutions fit the school's individual needs.

The Adolescent Pre-Diabetes Prevention Program assigns a regional coordinator to cover five or six schools. "They've been able to build really great relationships with the school administration as well as the faculty and staff, and they have great rapport with the kids," Cowart said. Many of the regional coordinators used to work in education, such as former teachers and principals. Another is a community outreach advocate at a hospital.

Each regional coordinator works with screening assistants who help with screening events and other school activities. Phlebotomists attend each screening to perform the blood draws.

Originally, the program worked with different organizations to create a curriculum and supplementary materials for the Healthy Lifestyle lessons but learned quickly that the students didn't connect with the material: "These kids throw that stuff in the trash so fast it'll make your head spin," Cowart said. The program then created its own curriculum that effectively resonated with the students.

In addition, the Healthy Lifestyle lessons focus on small changes that do not feel overwhelming to students. For example, Cowart said, "Instead of drinking that full glass of sweet tea, drink half sweet tea and half unsweetened tea." Lessons might also address finding healthier options at fast-food restaurants, convenience stores, and school canteens.

Lessons take about 15-20 minutes, so students aren't out of class for too long, and leave time at the end for students to talk privately with a coordinator. "The coordinators are always there to listen to them, to talk with them, and to provide them with individual guidance," Cowart said.

Building trust and gaining buy-in

In addition, the Adolescent Pre-Diabetes Prevention Program offers school employees an opportunity to participate in health screenings designed specifically for the faculty and staff. This offering helped coordinators build trust within the schools and gain buy-in for the program. Cowart said he has noticed a difference from the beginning of the program, when coordinators would struggle to get just a few parents to sign consent forms, to now, when school staff themselves encourage parents to sign the forms.

The screening events for staff are incentivized, with schools receiving a certain dollar amount based on how many employees participate: $500 for 60% participation, $750 for 70%, and $1,000 for 90%. "This year, we gave almost all of them a thousand dollars," Cowart said. "That speaks highly because we were struggling in the very beginning to give them $500."

Now, Cowart said when he attends a screening event, staff members approach him and ask when the next staff screening will be. This year, about 1,200 school employees completed a screening, which Cowart estimates is about 85% of school employees in the service area. He added that the screenings help people become aware of their health status and recalled two staff members whose blood pressure was so high that they were immediately taken to the hospital.

Another way that the program built trust with school staff was to shorten the time involved in the screening events. "In the beginning, we were asking the schools for a lot in that we needed them to help us round these students up and get them to a screening," Cowart said. "It was disrupting classes." Now, the screening events take 15-20 minutes per student.

Originally, the program anticipated being able to complete a finger stick test to determine students' A1C levels, but these tests are not allowed for diagnostic purposes — only for people who have already been diagnosed with diabetes. The program now uses intravenous blood draws to screen students.

Cowart said this was a challenge at the beginning since some students did not want to deal with needles. Now, he said, "We have become ingrained in the school…We are in and out of the schools all the time, and they know who we are and they trust us. So as that developed, we've had a lot less resistance to our jobs and the things that we do."

Another way the program addressed students' hesitation is by designing the screening events in an open manner, where students can see what goes on in every station while maintaining students' privacy as they talk to coordinators.

For any rural organizations looking to create a similar program, Cowart recommended finding organizations that have done something similar and using resources that already exist instead of creating something from scratch. "Reach out to others and don't be afraid to ask," he said. "People are proud of their programs and are more than willing to share."