Jun 12, 2024

Loneliness and Social Isolation Are Common in Rural America. Is “Social Infrastructure” the Solution?

In recent months, Dr. Hannah Fields, a family physician in Madison, Minnesota, has been running an informal trial for an unusual prescription: a visit to the local coffee shop. "It's as simple as pulling out a piece of scrap paper and writing a prescription for coffee, then texting Kris [the owner of the shop] like, 'Hey, if someone shows up with this, put it on my tab,'" said Fields.

The health benefits of moderate coffee consumption, while numerous and well-established, are not the primary motivator of Fields' experiment. Rather, she knows from personal experience that her patients, upon entering the Madison Mercantile, will likely be greeted by owner Kris Shelstad and offered a tour of the space, chat with the friendly baristas, and potentially even join one of the many groups that meet there throughout the week. These interactions, Fields believes, amount to an intangible elixir that is healthier and more invigorating than even the Mercantile's strongest brew: authentic human connection.

It's a basic — though often unacknowledged — necessity for health, "as essential to survival as food, water, and shelter," according to The U.S. Surgeon General's Advisory on the Health Effects of Social Connection and Community, published in May 2023. But across modern America, in rural and urban communities alike, connection seems increasingly in short supply. Issued in response to a worsening nationwide "epidemic of loneliness and isolation," the 2023 Advisory noted:

"Recent surveys have found that approximately half of U.S. adults report experiencing loneliness, with some of the highest rates among young adults. These estimates and multiple other studies indicate that loneliness and social isolation are more widespread than many of the other major health issues of our day, including smoking (12.5% of U.S. adults), diabetes (14.7%), and obesity (41.9%), and with comparable levels of risk to health and premature death."

When a 1964 Surgeon General's report warned of the health impacts of smoking, it set off a wave of education and policy efforts to encourage cessation. So far, the solutions proposed to our modern crisis of disconnection seem less straightforward — and many healthcare providers remain unsure of what role they should play. But one thing seems certain: as with smoking cessation effort, the distinct cultures and values of rural communities will likely necessitate a tailored approach.

I think that the first step — drawing on my background in substance use treatment — is admitting that there is a problem.

"I think that the first step — drawing on my background in substance use treatment — is admitting that there is a problem," said Fields. "The first step is admitting that if we are not addressing this with our patients, then we are not fully helping them." She hopes the 2023 Surgeon General's Advisory has opened the door for individuals and providers to reckon with the presence of these issues in their own lives, and in their communities.

As for the next steps, Fields is open to ideas — but believes the most successful approaches will involve community-wide collaborations. "It's all about bringing stakeholders to the table, realizing what resources are already [in the community], and how to more effectively partner," she said. Her referrals to the Mercantile are inspired by a practice, more common in Europe, known as social prescribing. While she has heard promising feedback from patients, she emphasized that formal program implementation and evaluation would be needed to draw any firm conclusions.

And the Mercantile, it must be noted, is no typical small-town café.

Coffee, Creativity, and Community

Kris Shelstad never expected to move back to Madison. In 2019, she was living in a suburb of Austin, Texas, and had recently retired from a long career in the National Guard. But after her husband passed away unexpectedly and the pandemic turned the world upside down, she sold her house and headed north to be closer to family.

At the time, she was reading a book that explored the common features of thriving small towns. It highlighted the importance of community gathering spaces for fostering cohesiveness, collaboration, and civic engagement. Additionally, "there was just a lot of discussion [in the media] about how isolated people were and the need for community, the need to bridge the divides," she said.

Taking stock of her new surroundings, Shelstad noted that Madison had a senior center, located in the basement of City Hall, but it wasn't functioning as "a day-to-day gathering space." There were a handful of restaurants, but Shelstad envisioned a place where there was "no pressure to buy something or turn the table, where you could sit all day."

The idea for the Mercantile started small. "My mother had a little coffee house many years ago, and I wanted to do something like that," said Shelstad. "But then an artist friend of mine from Texas passed away and left me about a hundred pieces of her work. So I took that as a sign from the universe that said: You're going to need a bigger space."

In 2021, she purchased a 15,000-square-foot building — a former building supply store, located in the heart of Madison's business district — for around $75,000. As she set to work converting the space into a café and community art gallery, locals would often wander in to ask about her plans. In response, Shelstad would ask them what they thought the community needed.

Ideas quickly accumulated: a stage for live music, a videoconferencing room for older adults to connect with faraway family members, a coworking space for remote workers and entrepreneurs, a local gift shop, a yoga room, a Men's Shed, and more. Because of the sheer size of the building, Shelstad just kept saying yes. She also formed a nonprofit, separate from the café, which allowed her to secure a fellowship and grant funding to support these various additional projects and uses of the building.

I think that in any town, the first thing you need to do is get the quilt club on your side.

After opening for business, she reached out to various community groups and invited them to use the building as a meeting space. "I think that in any town, the first thing you need to do is get the quilt club on your side," said Shelstad. With the help of these well-connected "creative ladies," more groups began showing up — and new groups soon took shape. Today, the building is host to a wide variety of weekly meetings: Bible studies, a cancer survivors' group, an environmental group, a coffee hour for Spanish speakers, and more.

Typically, when an unfamiliar face shows up at the Mercantile, Shelstad introduces herself and asks if she can show them around. Gradually, "they'll reveal what they're interested in, and then I'm like, 'You know what? We have a group that meets for that.'" She also acts as a community "matchmaker" — informally introducing individuals who she thinks should know one another. As for romantic matchmaking: "I think we've had a couple of successes there too," she said.

Shelstad admits that "some people would probably rather go to a truck stop where they can just grab coffee and go, because I accost everybody who comes in the door. Hi! Who are you? Where are you from? It's terrible!" This is more or less what took place when Fields first wandered into the Mercantile, shortly after she accepted a job at the local hospital in August 2022 — but she didn't mind at all.

Seeing the space and talking with Shelstad led her to recall a project she had worked on over a decade ago as a graduate student in Barcelona. Working with physicians in nearby rural communities, Fields had attempted to initiate a pilot program "to identify people who were either lonely or at risk for being lonely and try to get them set up with a formal prescription to participate in community activities." The program, however, struggled to gain uptake among providers.

"What I learned was something that didn't surprise me a whole lot, which is that the motivation and the drive to do these things is most effective if it's coming fully from within the community," said Fields. "You need champions that are within the community."

After meeting Shelstad and touring the Mercantile, she remembers thinking, "I want to support this woman and this organization — because this is the way to do it."

A Structural Approach

Rural America is sometimes characterized in the media and the popular imagination as a refuge from our modern crisis of disconnection, a place where most people — unlike a majority of their fellow Americans — still know their neighbors and enjoy a rich community life. Recent research, however, paints a more complicated picture.

Writing in JAMA Health Forum in 2020, Dr. Carrie Henning-Smith, Deputy Director of the University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center, noted: "While older adults in rural areas report having larger social networks than older adults in urban areas, they also report higher levels of loneliness, indicating structural barriers to connection." She identified "transportation challenges, built environments that are not always walkable or conducive to social interaction, more limited economic resources, less access to broadband Internet and cellular connectivity, and more restricted access to health care, including mental health care" as a few of these possible structural barriers.

According to Joanne Lee, Senior Project Director at Healthy Places by Design (HPBD) — a nonprofit that works with regional and national foundations to guide social connectedness initiatives — loneliness and isolation are often viewed as individual problems or even personal failings. But there is growing awareness of the structural factors contributing to widespread disconnection.

She sees parallels here with the progression of the public conversation around obesity and diet-related disease. "There was a time when the narrative was, 'Hey, just stop eating so much, go out and exercise!'" said Lee. "And then we realized that we need to look at the community environments and the policies behind them. Are there places for everybody to buy healthy foods or is it all fast food? Are there places for people to engage in more active living? Are there sidewalks and trails?"

Similarly, researchers and advocates working to address loneliness and social isolation have begun to focus less on individual choices and more on the strength of local "social infrastructure" — defined in the 2023 Surgeon General's Advisory as "the programs (such as volunteer organizations, sports groups, religious groups, and member associations), policies (like public transportation, housing, and education), and physical elements of a community (such as libraries, parks, green spaces, and playgrounds) that support the development of social connection."

Social infrastructure can also include private businesses like cafés and barbershops — and even radio stations and newspapers, which share information about local events. "It's the places where people connect and gather and are connected to resources within their communities," said Michael Stevenson, Co-Director of County Health Rankings & Roadmaps (CHR&R), an initiative of the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. "But it doesn't just stop at the physical spaces — it's also the underlying policies that nurture and support the investment in these spaces."

Earlier this year, CHR&R published a report examining the relationship between "civic infrastructure" — an analogous term — and local health outcomes across the country. The report noted: "The healthiest counties, where people live long and well, have well-resourced civic infrastructure…compared to the counties among the least healthy."

Stevenson emphasized that strong social infrastructure is characterized not by the presence of a single service or community organization, but is more akin to an ecosystem of opportunities for connection and participation: from community centers and libraries to public transportation and broadband. "And what the evidence shows is that when we participate, we actually have better self-reported physical, mental, and overall health," he said.

Compared to many other communities of its size, the social infrastructure in Madison is relatively strong. There are numerous churches, a beautiful Carnegie library, a community theater, and now the Mercantile, which serves as a de facto community center. If Fields were to expand and formalize her social prescription program, she thinks it would be important to partner with a wide range of local organizations in addition to the Mercantile.

She also sees room for structural improvements. For example: lately, Fields has been noticing a lack of sidewalk access in some areas of the community. And there is a cultural norm — common across the U.S. — of choosing to drive, even for very short trips. Fields believes that, if walking was both safe and culturally normalized, there would be more opportunities for people to bump into acquaintances as they went about their day. Even a greeting from a passing stranger can be good for our health, she said.

But the benefits of strong social infrastructure are not limited to improved individual health outcomes. As noted in Socially Connected Communities: Action Guide for Local Governments and Community Leaders, developed by the nonprofit Foundation for Social Connection, a partner of Healthy Places by Design: "Connected communities can also make small and mid-sized cities more competitive, adaptable, and resilient to demographic and economic changes."

According to Shelstad, the Mercantile has already "incubated two businesses," which have since relocated to other buildings in town. Recently, the Madison Economic Development Authority contracted with her nonprofit to represent Madison at conferences, write grants, and provide meeting space for the local business community.

"I told myself early on, if we're doing this right, somebody's going to move to town because we have this place," said Shelstad. "If they have a choice of western Minnesota communities, we want them to pick Madison."

Explore Your Local Social Infrastructure

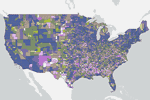

County Health Rankings & Roadmaps' 2024 National Findings Report includes an interactive map which can be used to explore three aspects of social infrastructure in every county in the nation: broadband access, local newspapers, and public libraries.

Around the Country

Despite her early successes, Shelstad doesn't generally encourage others to replicate her organization's model unless they have "spent 20 years in the Army and have a pension and health insurance." But more importantly, she insists that any effort to strengthen social infrastructure should be designed in direct response to the specific culture, resources, and needs of the local community. "I think, because of that, every one of these models is going to be a little bit different," she said.

In Gothenburg, Nebraska, response to community need led the hospital building itself to become a pillar of the town's social infrastructure. Since the completion of an expansion project in 2018, Gothenburg Health has been co-located with a YMCA. The facility includes a pool, gymnasium, exercise equipment, yoga room, and conference room — and offers afterschool and summer programming for local kids. The two entities are separated by a cafeteria.

According to Dr. Brady Beecham, Gothenburg Health Chief Medical Officer, the building is now a central gathering place for this town of 3,400. "On the weekends, there are all sorts of birthday parties that go on here," she said. "The kids go to the pool at the Y, then they come over and have their cake in the hospital cafeteria."

She recalled an experience from one of the first meetings she attended after stepping into her current role in 2023. It was a Monday morning, and a member of the leadership team was irritated by frosting he had found smeared on a table in the cafeteria. "I worked previously at a hospital where nothing like that ever occurred," said Beecham. "So the idea that we had this big problem of sticky frosting all over because it was such a community building — I was like, wow, that's a really interesting problem to have."

The unique arrangement emerged from a widespread community desire for more health and recreational opportunities for kids. There was strong support for a YMCA, "but we knew that one of the big hurdles to getting to the finish line would be just the significant cost," said Colten Venteicher, a local attorney who served on the steering committee for the project.

Hospital leadership, who were already planning a major expansion project, determined that "by co-locating it, not only could they basically cut [the cost of YMCA construction] in half, but they could also create some efficiencies by working together when it came to administration and overhead," said Venteicher. Construction costs for the YMCA portion of the building were supported by over $3 million in local donations, in addition to nearly $2 million in grant funding.

Venteicher says the facility has succeeded not only in expanding opportunities for kids, but in bringing together community members of all ages. "My wife plays pickleball with people in their sixties and seventies, and I have older clients who I'll see on the walking track," he said. "I've got four kids, and we use the YMCA almost every day. It's become a part of our family."

What I've learned is the necessity of sitting down and listening to people, truly taking that feedback to heart, and not being afraid to go back to the drawing board.

All frosting-related frustrations aside, Beecham says the hospital is quite happy with the arrangement — and continues to explore ways to act "as an extension of the life and needs of the community." Recently, the hospital, school district, city government, and others partnered to support the creation of a new facility, the Gothenburg Impact Center. It will house a childcare center, an indoor athletic turf, an event center for weddings and large meetings, and a centralized hub for various social services organizations.

As with the Madison Mercantile, this unusual combination of amenities was developed in direct response to community feedback. Venteicher, who serves as the president of the Impact Center's nonprofit operating entity, echoed Shelstad in his advice for other community leaders: "What I've learned is the necessity of sitting down and listening to people, truly taking that feedback to heart, and not being afraid to go back to the drawing board."

In the Matanuska-Susitna borough of Alaska — a rural area the approximate size of West Virginia — efforts to strengthen social infrastructure also began with a concern for local kids. "In 2016, there was a teen here who was murdered by other teens — and this obviously shook the communities pretty hard," said Tyler Healy, Director of Youth 360, a program of the United Way of Mat-Su. Multiple stakeholders coalesced to hold community listening sessions to explore what underlying factors might be contributing to teen substance use and criminality.

"One thing that came out of that process was simply — hey, teens don't have a lot of natural places to gather outside of school," said Healy. He noted that, while there are a few population centers in the borough, many residents live "very spread out — in the woods, to some degree."

Youth 360, the program that formed in response, operates three free afterschool and summer youth clubs: two located on school campuses and one held in a building owned by a neighboring church. Students are offered transportation back to their homes after the clubs close each day, eliminating a major barrier for many local families.

Students living in a part of the borough not served by an existing club — or who choose not to participate for some other reason — are offered scholarships to cover the cost of activities offered by "trusted community partners," ranging from music lessons to athletic leagues and martial arts classes. The program design is based on the Icelandic Prevention Model, which emphasizes expanded recreational opportunities and community-wide collaboration to prevent teen substance use, mental health problems, and antisocial behaviors.

Youth 360 is funded in part by the Mat-Su Health Foundation, which works with Healthy Places by Design to strategize their investments in social connection-related initiatives across the borough. They also operate several in-house programs, including Connect Mat-Su, a centralized resource and referral hub. The free service is used primarily for referrals to housing, transportation, and food access resources via email, phone, text, and in-person interactions. But "as we're talking to people, we're definitely picking up on cues about social isolation and making sure that they know about available resources if they're interested in them," said Connect Mat-Su Director Ashley Peltier.

For example, if an older adult calls regarding food insecurity, "we'll connect them to the local senior center as a place for food, but also as an opportunity for social connection," said Peltier. "If it's a young parent contacting us, we can get them connected to providers, but we'll also talk with them about Head Start programs, upcoming community events, and parent groups."

While the referral service assisted around 1,500 individuals throughout 2023, Connect Mat-Su is reaching even more locals through a piece of digital social infrastructure hosted on their website: a regional events calendar. Program staff update the calendar with events they learn about from partners, through social media, or through an online submission form. "In 2023, we had 50,000 unique users on our website, and the number one thing they were looking at was the events calendar," said Peltier. "So that tells us people are looking for social connection."

According to Stevenson at CHR&R, simply attending more community events can be a great first step for individuals and organizations looking for ways to strengthen their local social infrastructure. As exciting and impactful as new programs and facilities can be, it is equally important to support the local programs and infrastructure that already exist. "It can be as simple as supporting your local library," said Stevenson. "So going there, attending the events, and making sure it has the resources it needs to be successful."

"We don't have to solve all of these problems at once," he said. "Small steps are noble and a great place to start."

Join the Conversation

Healthy Places by Design has worked with local communities and those who invest in them since 2001, focusing on the environments, policies, and systems that either create barriers or opportunities for people to engage in healthy behaviors. Their recently launched Socially Connected Communities Network offers webinars, discussion groups, resource guides, and networking opportunities for individuals and organizations working to enhance social connectedness in communities across the country.

A Place to Feel Welcome

In our era of simultaneous public health crises — from obesity and loneliness to opioids and teen mental health — it can be easy for healthcare providers and community leaders to become overwhelmed, and Fields is no exception. But she finds it helpful to remember that all of these problems — and their potential solutions — are overlapping and deeply intertwined. Improving sidewalk access, for example, can expand opportunities for social interaction while also encouraging an active lifestyle. Community events and gathering spaces can foster meaningful social connections, which serve as a preventive factor against the development of substance use disorders and mental health conditions.

In order to respond effectively to these overlapping crises, Fields thinks it is important for the healthcare sector to acknowledge that health is "not merely the absence of disease or infirmity," as stated in the Constitution of the World Health Organization. "A patient can look perfect on paper, just because their blood pressure is controlled," she said. "But if they are absolutely miserable and totally alone, does that mean they're going to be okay in five years? No, they could be dead unless something changes for them."

Fields doesn't formally screen her patients for loneliness and social isolation — though such tools do exist. Rather, she makes her referrals to the Mercantile based on subtle cues and things that come up in conversation. If a patient is a new parent, a caregiver, or has recently moved to town, for example, she knows they may be more likely to benefit from the referral.

Two years after opening in this community of 1,500, Shelstad still often sees unfamiliar faces walk through the doors of her unusual establishment. They find their way to the Mercantile through a referral from Fields, an invitation from a friend, or of their own accord. Recently, a young woman showed up — a referral from Fields — who didn't speak much English. "She needed help hooking up her internet, so we used Google Translate and tried to help her," said Shelstad. "She's been in two or three times since then, and she feels comfortable now coming in with her little girl."

On a few occasions, women have walked in and asked for a quiet place to spend a few hours. "I don't know what the situation is, if they're just upset or if they felt like they weren't safe," said Shelstad. "We don't ask many questions."

Lately, more local teenagers have been showing up. Shelstad described the group as perhaps "a bit atypical in their looks or hobbies or whatever." They may be drawn in by the rotating local art exhibits or the tall stacks of strange old books, but most likely just the copious space to hang out with friends. A few months ago, a teenager — new to the community — walked in and said, "People told me I would feel comfortable here."

"And I just about cried," said Shelstad. "I was like, of course. Yes, of course."