Jul 13, 2022

Wiping Away the Tears: Addressing Increasing Death in Rural America

by Whitney Zahnd, PhD

There is a familiar saying:

Statistics are people with the tears wiped away. Many

tears have been shed in recent years, particularly in

rural America. The statistics are heartbreaking,

sobering, and affect persons of every age. According to

the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in

2021, the United States experienced the highest number of

deaths on record due in large part to the ongoing

COVID-19 pandemic and drug overdose epidemic. In 2021

alone, provisional numbers indicate that more than

415,000 Americans died due to COVID-19 — roughly

equivalent to the population of Tulsa, Oklahoma. In May

2022, the United States surpassed the sobering mark of 1

million COVID-19 deaths, with

nearly three-fourths occurring among those 65 years of

age or older. Further, a record number of Americans

died due to drug overdoses in 2021; the Kaiser Family

Foundation reports that greater than

80% of opioid overdose deaths are among persons under the

age of 55. The combination of a viral pandemic and

drug epidemic among other impacts has led to a

two-year drop in U.S. life expectancy from 78.85

years in 2019 to 76.44 in 2021, according to a preprint

article. Further, the United States has persistently had

higher rates of

infant and

maternal mortality rates compared to similarly

affluent countries.

There is a familiar saying:

Statistics are people with the tears wiped away. Many

tears have been shed in recent years, particularly in

rural America. The statistics are heartbreaking,

sobering, and affect persons of every age. According to

the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in

2021, the United States experienced the highest number of

deaths on record due in large part to the ongoing

COVID-19 pandemic and drug overdose epidemic. In 2021

alone, provisional numbers indicate that more than

415,000 Americans died due to COVID-19 — roughly

equivalent to the population of Tulsa, Oklahoma. In May

2022, the United States surpassed the sobering mark of 1

million COVID-19 deaths, with

nearly three-fourths occurring among those 65 years of

age or older. Further, a record number of Americans

died due to drug overdoses in 2021; the Kaiser Family

Foundation reports that greater than

80% of opioid overdose deaths are among persons under the

age of 55. The combination of a viral pandemic and

drug epidemic among other impacts has led to a

two-year drop in U.S. life expectancy from 78.85

years in 2019 to 76.44 in 2021, according to a preprint

article. Further, the United States has persistently had

higher rates of

infant and

maternal mortality rates compared to similarly

affluent countries.

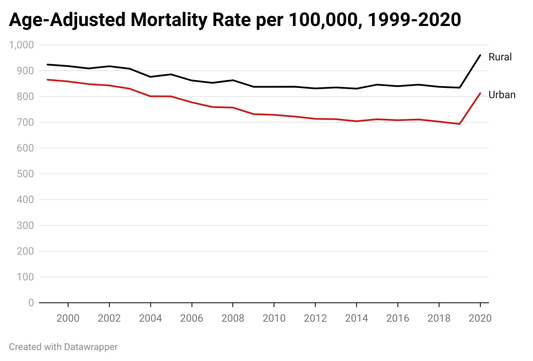

Across rural America, mortality disparities are particularly stark compared to their urban counterparts, which have been intensified by the pandemic. At the 2022 National Rural Health Association meeting, Jan Probst, Professor Emerita at the University of South Carolina and Director Emeritus at the University of South Carolina Rural Health Research Center, presented analyses of rural-urban differences in mortality. Rural populations persistently had higher age-adjusted mortality rates than their urban counterparts, and experienced slower declines in mortality compared to urban with a roughly 10% decrease in death rates in rural between 923.8 to 834.0 per 100,000 between 1999 and 2019. Meanwhile, urban areas experienced an approximately 20% decrease in mortality rates. Additionally, in 2020, rural mortality rates increased to 960.3 per 100,000; all improvements in rural mortality were wiped away by the first year of the pandemic, according to Probst's analysis. Although COVID-19 was the largest contributor to these increases, Probst also noted that deaths due to accidents, alcohol, and other drugs increased more than 30% in 2020 among both rural and urban adults aged 25 and older.

While persistent rural mortality disparities might be our past and present, they do not need to be our future. There are many solutions to stem the tide of rural mortality. Probst notes, "Let's get real — we live in a market-based economy. That's how we have chosen to set ourselves up. Therefore, there are some problems you can fix by…making sure there is enough money available to provide minimum levels of services." Past and ongoing investment in rural health in America has the potential to slow or reduce disparities in COVID-19 deaths; opioid and other drug-related deaths; and deaths among moms, infants, and children.

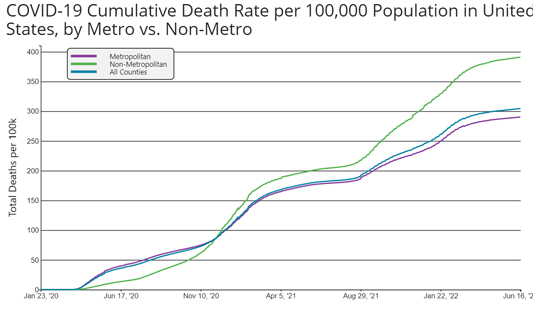

Stemming the Tide of a Pandemic that Hit Rural America Later, but Harder

As with many diseases, COVID-19 hit rural America later, but it hit rural America harder. For most of 2020, the cumulative death rate due to COVID-19 was higher in urban (metropolitan counties), as shown in the graph below from the CDC. However, since mid-December 2020, the cumulative death rate in rural America has exceeded that in urban. As of June 16, 2022, roughly 100 more people per 100,000 in rural areas have died compared to urban despite having lower cumulative case rates according to analysis from the RUPRI Center for Rural Health Policy Analysis.

Probst notes three overarching reasons for these disparities including differences in "non-pharmaceutical interventions" like mask-wearing, as well as access to and uptake of COVID-19 vaccines and access to acute care like hospitals. She noted that "once one has acquired the illness, the resources that are available in rural counties are lower." Many rural populations have a higher risk of severe disease due to COVID-19, which has had the potential to put greater strains on hospitals. Probst's research highlights that rural older adults were less likely to engage in risk mitigation behaviors during the summer of 2020.

In the past year and a half in particular, through the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the federal government has provided billions of dollars to Rural Health Clinics to address COVID-19 through testing and mitigation programming and efforts to distribute vaccines and increase vaccine confidence in rural areas. These funds allow RHCs to provide a myriad of services, such as home testing kits and vaccines, and support a host of programs to support these efforts, including allowing funding to be used for staff retention bonuses, patient transportation, HVAC system upgrades, and long COVID support. Shannon Chambers, Director of Provider Services with the South Carolina Office of Rural Health and Secretary/Treasurer with the National Association of Rural Health Clinics, applauds the innovativeness, resilience, and partnerships created by RHCs to tackle these challenges, noting that RHCs have used these federal funds to make modifications to their clinics: "Changing out water fountains for water bottle filling stations for infection control. Really looking at those high-touch areas of the clinic… Bathroom sinks, toilets, et cetera, adding foot openers on all doors so that you don't have to touch the handles of the door."

The Drug Overdose Epidemic Hits the Rural Midwest

While opioid-related death rates are higher in urban areas, the largest increases in opioid-related deaths in recent years have been in rural counties, particularly in the Midwest. The percentage of rural patients with an opioid prescription is higher than among urban patients. However, the drug overdose epidemic in rural areas is complex. Large increases in drug overdose deaths are due in part to the increasing availability of the potent drug, fentanyl. Fentanyl's medical use is for chronic severe pain or for severe pain following a medical procedure. However, it has also been illicitly manufactured and mixed with other drugs to increase their potency and has become a key driver in drug overdoses. Further, there has been an increase in polydrug use, and the use of methamphetamines is also on the rise. Misuse of opioids and other drugs is further complicated by the syndemic effects (that is, the concurrence of two or more epidemics with biological interactions) of infectious diseases caused by sharing needles in intravenous drug use. Infamously, in 2015 and 2016, rural Scott County, Indiana, experienced an HIV outbreak of more than 200 HIV cases, many with co-infection of hepatitis C, in a county of roughly 4,200 residents — due largely to the sharing of needles among injection drug users.

2023 Editor's Note

In 2023, the waiver requirement was eliminated with the passage of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023. This allows any provider with a DEA Schedule III prescribing privilege to automatically prescribe buprenorphine for OUD — if allowed under the individual provider's state law.

Wiley Jenkins, a research professor in the Department of Population Science and Policy at Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, notes that Drug Addiction Treatment Act (DATA) waivers can enable practitioners to prescribe buprenorphine, a drug that can help patients with heroin or methadone dependence, but the availability of providers has not always translated into access to these treatments. Jenkins notes that even if a physician has a waiver, they sometimes require patients to meet a certain criterion, such as having a toxicology assessment, before they prescribe such medication to a patient. Other barriers include patient transportation and limitations in the number of patients that a practitioner can prescribe to in a given year.

Over the past several years, several federal agencies have invested millions of dollars in addressing this syndemic in rural America. For example, in 2017, the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), in collaboration with the CDC, the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services (SAMHSA), awarded millions of dollars in funding for communities to address the complexities of opioid and other substance use disorder in conjunction with injection-related infectious diseases. Jenkins and Mai Tuyet Pho, MD, an infectious disease physician at the University of Chicago, received one of these awards to address the opioid epidemic's effects in rural southern Illinois. Through these efforts, they have been able to partner with Community Action Place, a harm reduction organization that helps reduce the practice of unhealthy drug use and sexual behaviors and provides treatment referrals through the provision of mobile services that meet people at their homes, health fairs, and food banks. HRSA has also allocated funds through their Rural Communities Opioid Response Program (RCORP) for program planning and implementation, medication-assisted treatment expansion, neonatal abstinence syndrome, and psychostimulant support.

Persistent Disparities in Infant, Child, and Maternal Mortality

Rural-urban disparities in mortality extend beyond recent epidemics and pandemics and affect those of all ages. Rates of infant mortality have been persistently higher in rural areas compared to urban. Studies also show that rural women have a greater probability of severe maternal morbidity and mortality compared to their urban counterparts, though rates are increasing in both populations. Rural children and adolescents also consistently experience higher mortality rates compared to their urban peers with particularly stark disparities in deaths due to unintentional injury and suicides. Lack of access to care likely plays a key role in these disparities. Studies show that more than half of rural counties do not have available obstetric services, a proportion that continues to grow as hospitals forgo their obstetric service line. This has led to pregnant women needing to drive 90-100 miles to a hospital with labor and delivery services in some areas like rural Wyoming which experienced two hospital closures this past spring. Similarly, lack of access to mental health and trauma services in rural areas perpetuates child mortality.

Through its Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB), HRSA invests in several programs to improve the health of women, infants, and children in rural areas and beyond, such as the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) Program, Healthy Start, Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM) Initiative, State Maternal Health Innovation (State MHI Program), and the Remote Pregnancy Monitoring Challenge. Further, HRSA just released final criteria for a Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) designation for Maternity Care Health Professional Target Areas (MCTAs). These designations will identify areas among HPSAs where maternal healthcare services are needed, which would enable National Health Service Corps practitioners who provide maternity services to practice in these areas.

The Path Forward

Through its programming, HRSA is helping to address the workforce and resource needs of communities, clinics, and practitioners in rural communities that may help stem the tide of increasing rural disparities in mortality, but more work is needed. Continued investment in rural hospitals and clinics are needed to ensure that rural residents have access to the necessary care to address the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic; prevent and mitigate the effects of drug overdoses; and ensure that rural moms, infants, and children receive the care that they need. The financial viability of these hospitals will require payment systems that reflect the unique needs of rural hospitals that provide necessary care to a smaller number of patients than urban hospitals. Rural hospitals, clinics, practitioners, and residents are already resilient and innovative, but continued investment and targeted resources are needed to ensure they can address their unique needs.

Opinions expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Rural Health Information Hub.