Jul 24, 2024

Rural Community Health Worker Programs: Proving Value and Finding Sustainability

Community health workers (CHWs): a workforce with much recent attention, including a 14% occupational growth rate over the next decade, an estimation provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Why such attention?

Experts said it's likely due to this workforce's core work of managing the non-clinical drivers of health and well-being, better known as the social determinants of health (SDOH). However, adapting CHW work as a standard of care is complicated by what researchers describe are the costs that, "unlike standard medical care in clinics or hospitals, often require considerable transportation time, mobile equipment, and associated expenses, alongside flexible systems for supervision and support to ensure safety of CHWs and effectiveness in delivering roving, within-community services."

Specific to rural healthcare, previous research demonstrated CHW services are cost-effective. Additional research is in progress to further evaluate their potential "to improve the bottom line for health systems in rural communities across the United States."

Another rural-specific financial challenge for implementing CHW services comes with providing care for Medicaid beneficiaries. A recent academic analysis found "the threshold minimum levels of both Medicaid FFS [fee-for-service] and PMPM [per-member-per-month] payments estimated through our microsimulation model to sustain CHW programs were typically much higher than those currently publicly disclosed by Medicaid officials." Other financial challenges exist for Accountable Care Organizations or other groups transitioning to value-based care. Sustainability planning for CHW programs can be difficult as payment for CHW services evolves, but sometimes the news is good: As of January 2024, Medicare, too, is now offering some CHW services reimbursement in the form of "incident to" payments linked to community health integration services.

Despite the programmatic financial challenges, four rural organizations from across the country — including an established West Virginia model with a nearly four-year record of financial sustainability through a unique reimbursement structure — shared the impact of their CHWs' work for their patients, their organizations, and their communities.

To Start: CHW Definition, Rural Roles

Although the community health worker (CHW) is a globally recognized professional, some researchers note that their occupational identity lacks universal definition. Experts said the most frequently referenced definition is that created by the American Public Health Association:

"A community health worker is a frontline public health worker who is a trusted member of and/or has an unusually close understanding of the community served. This trusting relationship enables the worker to serve as a liaison/link/intermediary between health/social services and the community"

In rural America, CHW work has flexed with the needs and goals linked to their volunteer or employed roles. Building on the long-standing work of the promotoras or promotores de salud in Spanish-speaking communities and the tribal Community Health Representative, one report (no longer available online) discovered that currently, in rural America, the CHW is most likely to be a "generalist," compared to the specialty focus of an urban CHW. Exploring the generalist role further, a rural-based CHW program will often include elements representative of common models, ranging from clinical team membership to outreach and health educator — or to even impacting their communities in the role of a community organizer and capacity builder.

| Rural Community Health Worker Models | |

|---|---|

| Model | Role |

| Care delivery team member | Assists with non-medical needs that impact medical conditions |

| Care coordinator/case manager | Provides healthcare system navigation assistance |

| Screening and health educator | Provides health screenings and topic-specific health education |

| Outreach and enrollment specialist | Provides information for needed resources and program enrollment assistance |

| Community organizer/capacity builder | Provides community coordination for designated issues |

| Source: Community Health Workers Toolkit | |

One of the First: An Outreach and Enrollment CHW Model in Northeastern Vermont

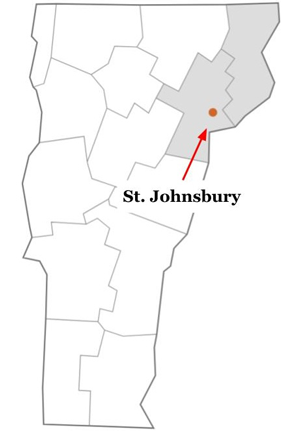

In St. Johnsbury, Vermont, the Northeastern Vermont Regional Hospital (NVRH) and its system of several Rural Health Clinics (RHCs) serves a two-county area with a 33,000-plus population. A decade before the implementation of the 2010 Affordable Care Act, the community's physicians were already recognizing that their patients had needs impacting their health and well-being which were outside of what they as physicians trained in physical and brain health could address.

"Those providers saw how the needs of someone without housing or enough food or enough money to make ends meet were impacting their patients' health," NVRH's Community Health team lead Deborah Locke-Rousseau said.

Locke-Rousseau shared more about the history of the organization's early adaptation of the CHW model.

"Again, without clear specifics at the time, what they were actually asking for was someone to do this piece around the health-related needs of their patients that they weren't able to do," she said. "That's how the CHW effort started in our health system back around 2002."

Diana Gibbs, NVRH's vice president of community health improvement, pointed out another aspect of that original request.

"Those providers recognized that the most valuable assistance would probably best be provided by someone trusted, someone with roots in community. Someone who could walk the walk and talk the talk."

Locke-Rousseau said those elements made the CHW model an ideal fit for the community's needs. Still a working CHW model today, the St. Johnsbury model has been studied and its results frequently cited, including the early program's startup costs.

Locke-Rousseau and Gibbs described NVRH's current CHW program, called Community Connections (CoCo). CoCo primarily works as an efficient and effective community outreach and enrollment specialist model. For example, the CHWs provide assistance with health insurance enrollment, yet also connect clients with needed resources for utilities, food, and transportation. Representative of rural CHWs' role flexibility, Locke-Rousseau said that CoCo CHWs are certainly adept at what is considered a rural CHW's generalist role.

"CoCo's CHWs are office-based and appointments are available to everyone in our community," Locke-Rousseau said, noting that the CHWs serve an average of nearly 7,000 unique clients each year. "We also respond to the need of our hospital coworkers along with our clinical and non-clinical community partners. When needed, the CHWs do leave the office to do a home visit. During COVID, however, we learned we could do some of our work differently and with great efficiency over the phone."

Shawn Tester, serving as NVRH's CEO now for over five years, said that some of the program's funding comes from Blueprint Vermont for Health, a state model that "designs community-led strategies for improving health and well-being."

"CHWs provide important services, but what's often lost on federal and state agencies providing support is that the assistance mostly happens one person at a time, making the CHWs' work very, very difficult to quantify in terms of cost," Tester said, noting that other than Blueprint Vermont for Health, funding streams are getting fewer and smaller in amount, recently forcing them to decrease staff from five to three.

"To cover the costs becomes almost an existential challenge," he said. "We constantly try to restructure the model, even eliminating any profit margin, to just make enough money to cover the program costs, especially with current inflation issues. Funding this valuable work is definitely the big disconnect."

NVRH leaders shared that they've had no difficulties with CHW recruitment or retention and indicated they're hopeful that the Vermont Community Health Worker Steering Committee's Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-funded research will lead to a new state CHW strategy that includes sustainable support.

CHW Reimbursement Policies and Certification Benefits and Controversies

The National Academy for State Health Policy tracks state-specific CHW policies, including CHW definitions, reimbursement, and training and certification information. CHW certification is another area that involves some controversy. In its 2020 report, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) gathered stakeholders' views around both the benefits and unintended consequences of certification. State policies are continually changing, and a 2022 academic publication provides a review of U.S. funding, payment, and reimbursement laws.

Idaho's Model: CHWs Creating Community Trust — and Much More

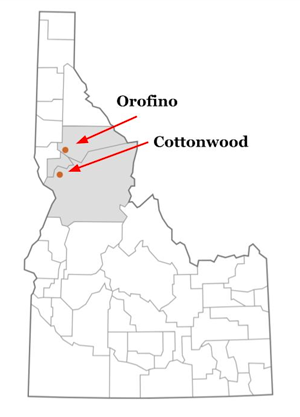

Idaho's state motto is "esto perpetua": Let it be perpetual. Although currently sustained by internal funding, that is the goal of Cottonwood and Orofino's St. Mary's Health and Clearwater Valley Health for their much-studied CHW model: to eventually have permanent funding support. With two Critical Access Hospitals and eight clinics, the organizations serve around 30,000 individuals in three Idaho counties where the population density is around 2.5 people per square mile in an area the size of Massachusetts.

Cody Wilkinson, director of population health for the organizations, oversees the CHW program that replicates elements of several of the rural CHW models. He said that, currently, the health systems employ five geographically located CHWs. He also reports no attrition in these positions in the past several years. Idaho requires no certification and the organizations rely on CHW training provided by Idaho State University with additional community-focused training through their own health system. In their model, CHWs are outpatient-based. Like the Vermont program, colleagues — for example, the discharge planners — from the hospitals can attend weekly huddles and bring attention to patients needing services.

"Our CHWs are strategically located so the nooks and crannies of our service area are covered," Wilkinson said. "Because CHWs do not have clinical training, they don't do physical exams. Instead, I consider them to be community connectors. They represent our organization and the resources in our hospitals, our clinics, and in the community and take that information from inside our system to the communities where people live. Our CHWs strive to ensure our communities have both the resources and knowledge to take care of themselves."

Adding that a five-year philanthropic grant helped "hone" their CHW program's work and focus, Wilkinson said, "We prioritized the CHW program and now see its impact. In my opinion, it's an extremely valuable service to be able to offer to our communities."

In 2023, four academic publications reviewed the Idaho model:

- Rural Healthcare Disparities in the United States: Can Our Payer Structures Help Us Get Upstream?

- New Frontiers in Diabetes Care: Quality Improvement Study of a Population Health Team in Rural Critical Access Hospitals

- Financial Sustainability for Complex Care Models Serving Low-Income Patients: a New Role for Philanthropy

- Trust Dynamics of Community Health Workers in Frontier Food Banks and Pantries: a Qualitative Study

Wilkinson said that the most commonly leveraged task within their CHW model is SDOH assessments and providing assistance with food and transportation. He said they've learned from their community members that although they were reluctant to check certain boxes on a SDOH screening form, after having done so, they found themselves very grateful for the follow-up assistance received.

Idaho CHW activities

Perform community health screenings

- Blood pressure checks, finger prick labs like hemoglobin A1Cs

Organize and moderate community health education sessions

- Example: "Living Well" series

- Special speakers engaged by the CHWs

- Topics:

- Fall prevention

- Anxiety management

- Advance Care Planning themes

- Insurance products

SDOH assistance

- Transportation

- Housing

"We've discovered that when we're able to follow up on social determinants of health issues that show up with screening, we can help people figure out a solution," he said. "In addition, that effort itself actually helps build trust and rapport with our community. Most rural healthcare organizations inherently understand the strategic importance of gaining their community's trust. This program builds on that trust. As an organization, we are highly invested in this program. We consider our CHW program to be a great success, and we will continue to strive to find ways to sustain it."

In Arkansas: Federal Funding Brings "Overwhelming" Success

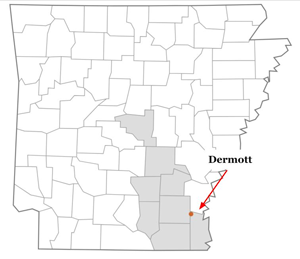

Having its 1978 origins linked to the work of a volunteer physician and a volunteer nurse, Mainline Health Systems, Inc. (MHSI) Dermott, Arkansas, is a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) with 35 locations serving eight counties.

Allan Nichols, MHSI's CEO, shared the backstory about leveraging a federal rural grant to support the development of a CHW program in three of their service area counties.

"We are a very high-performing FQHC," he said. "We win all kinds of quality awards, year over year. Yet, we understood there was a small group of our patients that continued to impact our ability to move our quality needle higher. What we knew about those patients is that they had complex problems and complex lives. We also suspected we needed to better understand those complexities in order to make a difference for those patients. Looking down the road at what DePaul Community Health Centers in New Orleans was accomplishing with their community health worker program convinced us to implement a similar program for our patients."

Ashley Anthony, MHSI's chief operating officer, shared results from their CHW program, currently supported by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy's 2021-2025 Rural Health Care Services Outreach Program grant, that's representative of CHWs acting as generalists and members of medical teams.

"When we started our program in 2021, we were just post-COVID," she explained. "Because our CHWs go into the home, there was some initial hesitation on the part of the CHWs and the patients. However, it didn't take long to gain trust. Much is learned with home visits. For example, making the discovery that a person has a disability that actually prevents them from leaving their home — a challenge not previously revealed to our medical providers. But CHWs handled that problem. They engage the services that get a ramp built. Now, transportation needs and mobility options are available to the patient and family. And that's just one of the many examples."

Anthony shared another anecdotal outcome in the early stages of their grant-funded work: Organization-wide immediate buy-in of the CHWs' work.

"Our initial grant-funded CHW workforce was for locations in three of our service counties," she said. "But almost immediately our CHWs were getting referrals from every clinic, every case manager, and almost every provider in our system. We quickly embraced that engagement. Our electronic health record and care coordination workflows with case managers and others allowed quick integration. With such positive outcomes, there's solid support for the CHWs' work system-wide."

Integrating CHWs With Other Healthcare Professionals

Although MHSI's program experienced almost immediate system-wide acceptance of their new CHW, previous FORHP-funded research had found that integration usually progresses through three stages: lack of knowledge and understanding of CHW roles, conflict and competition, and then engagement and integration.

Nichols said his greatest surprise was the immediate and profound impact on outcomes.

"By end of our first cohort? Not one hospital admission or ER visit," he said. "This CHW program demonstrates that we need to throw away the idea of what we 'should do' for patients and replace it with what CHWs 'can do,' especially when it comes to managing the social determinants."

Nichols describes a similar perspective in alignment with Vermont's Tester: CHW successes create an "existential challenge" around financial sustainability.

"Early on in this grant, we realized that we were developing an actual dependency on CHWs," he said. "But in Arkansas, there is no revenue stream for their work despite our grant work revealing that the financial savings were much, much greater than CHW costs — actually showing an overwhelmingly high return on investment. That's a result that we'd hope CMS [Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services] would see as valuable and pay for. Per-member-per-month payment or shared savings plan could be options."

Breaking the Financial Sustainability Barrier: West Virginia's Rural CHW-based CCM Model

A 2017 research review of study data through 2015 pointed out the impact of CHWs: Cost savings could be realized as long as CHWs were not a stand-alone intervention, but specifically integrated into chronic care management. According to a 2022 Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) CHW-specific brief, Michigan was the only state requiring CHWs in team-based health home programs. The report also highlighted five states — California, Maine, Michigan, Washington, and West Virginia — now allowing formal CHW participation in those teams. A closer look at a West Virginia model finds a long-running rural CHW-based program that has a four-year track record of financial sustainability: the CHW-based chronic care management program model (CHW-based CCM).

Key Elements of the Community Health Worker-based Chronic Care Management Program (CHW-based CCM)

- Creates both a new rural workforce and a sustainable business model for that workforce

- Allows payers to engage in a multifaceted role:

- Provide patient participation incentives

- High-risk patient identification

- Collaborative case management

- Reimbursement structure

- Per-member-per-month

- Annual shared cost analysis

- Includes an integrity partner's data collection

and shared analysis at regular intervals

— especially HEDIS measures

- Fosters organizational performance management and quality improvement

- Allows another point of engagement with payers

- Demonstrates consistent success with 3 model

fidelity elements:

- Provider champion

- Weekly huddles

- Weekly home visits until medical and linked SDOH conditions are stable

"Over the last decade, this program has matured to not only include a business plan, but essentially creating a new rural health workforce for West Virginia," Deborah Koester, PhD, DNP, said, sharing key elements of the model.

Koester, director of the Community Health Department at West Virginia's Marshall University Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine, described how, over the course of the model's development, Marshall University has provided training, technical and implementation assistance, and data analysis and acted as an integrity partner.

However, as a nurse practitioner, Koester also shared her clinical perspective.

"Central to our model is that it is a clinical model," she said. "The community health worker, in addition to doing all those things linked to addressing social determinants, is also teaching chronic care self-management skills that can lead to healthier patient behaviors. That offers a big benefit: Patients who better self-manage reduce hospitalizations and other healthcare costs."

Program leaders shared the evolution of this model. Integral to its development was initial philanthropy support, in particular, the Claude Worthington Benedum Foundation. Kim Tieman, Benedum's vice president and program director, said she's been involved with the model since its early implementation, including a FORHP public-private partnership grant. Echoing the thoughts of CHW model leaders in Vermont, Idaho, and Arkansas, Tieman said the strength of this model is exactly that: the CHW.

"Around the country, the CHW worker title and role receive recognition, but what CHWs can actually accomplish in rural areas does not," Tieman said. "This CHW-based chronic care management model demonstrates that unique potential of the CHW — and we have more than a decade of data to prove it."

Additionally, Koester and Tieman said for any CHW model to gain mainstream acceptance, it has to have financial sustainability. Currently, the rural CHW-based CCM model might be the only model with an embedded sustainability business plan. Over the past four years, sustainability has come from several West Virginia Medicaid managed care plans' per-member-per-month support.

Tieman said a key to payer support was linked to early payer participation in the model's grant-supported development: Payers were invited to attend grantee update meetings. This allowed them an "inner circle seat" where they could understand the working parts and mechanics of the model, especially the elements specifically delivered by the CHW.

"Remember, despite the fact that payers do their own proprietary quality analysis and have their own case manager jurors and underwriters, they still want to hear about innovation," Tieman said, adding that a common interest of payers and organizations using CHW-based CCM was monitoring HEDIS measures. "Convincing them to be at the table to hear the real-time conversations about what was working and what wasn't became valuable to them, especially in terms of understanding CHW efficiencies and effectiveness."

Koester and Tieman said the model has matured to the point where replication is now becoming routine. As of July 2024, 50 CHWs are working in 31 counties and three states.

Marshall's Koester shared that the model now includes a projection tool. Analyzing data such as operational costs, potential patient panel numbers, and number of CHW visits, this tool can provide an organization with a revenue estimate.

However, model leaders said that "absolutely mandatory" for success is model fidelity — making sure there is a physician champion, weekly huddles, and weekly CHW visits.

With regard to the weekly CHW visits, Tieman, a social worker herself, said that a decade-plus of CHW-based CCM analysis has provided insights.

"We've learned that the absolute value of the CHW visit comes with 'going through the door, not to the door,'" she said, acknowledging that only infrequently has safety precluded the intimacy of that type of visit. Akin to Vermont NVRH Tester's observation that the CHW-client interaction is hard to quantify in terms of cost, Tieman also observed that the impact that comes from sitting face-to-face with the patient is hard to monetize but must be if CHW models are to gain mainstream use.

From a West Virginia Clinician: The Professional Impact of the CHW-based CCM Model

Asked to submit a Grant Makers in Health (GIH) blog post earlier this year, Tieman described an initial achievement for their CHW-based CCM program: alignment with the Institute of Health Improvement's Triple Aim goals of improving the individual experience of healthcare, improving population health, and reducing healthcare costs.

Yet CHW-based CCM advocates suggested that this model may go one step further and align with those who propose the Quadruple Aim, adding improved work life of healthcare providers to the goals of the Triple Aim.

How is this fourth aim achieved by the CHW-based CCM model? As did the Vermont providers 25 years ago, today's providers recognize that addressing their patients' SDOH needs are not always within their skill set. Over time, to continually be able to only deliver clinical care — care that is such a very small percentage of what impacts their patients' health and well-being — impacts clinicians' career satisfaction and their personal well-being. In other words, coming up short for patients doesn't foster a clinician's professional satisfaction.

Jerome Cline, FNP, native West Virginian, and certified diabetes specialist, is one clinician who's been involved with the CHW-based CCM program from its early grant-funded days. He shared how the model has come to positively impact his philosophy of providing patient care.

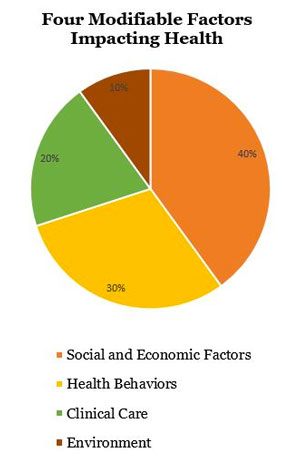

"Working with the model for the past decade, I've learned that it's the one program that allows us to focus on the 80% of those non-clinical influences on health," Cline said, referencing the four modifiable factors impacting health.

"It's also the one program that allows us to have upstream impact," he further pointed out. "Back as early as the 1960s, research was showing that moving healthcare's focus into the home was where upstream value happened. Research continues to support the value of working upstream and no program shows greater impact than those that include CHWs. With CHW-based care comes clinically significant improvements, reduced complication rates, and lower readmission rates. Most important is that the research also shows that patients regain control of their lives. These things add a great deal of professional satisfaction to the daily work of patient care. For me, the professional and personal satisfaction we experience working with this program seems to have a way of influencing the entire care team."

And research suggests that these are the variables that influence rural clinician well-being. Cline shared more concrete program influences on his daily workflow.

"There are many time savers that come from our CHW model," he said. "Directly impacting our work is how their electronic documentation helps streamline my patient narrative documentation. Another example? They often have to dedicate a lot of time getting an accurate account of a patient's medications. Having gone 'through the door,' they'll discover that patients with several chronic conditions who are seeing several specialists often have different medications prescribed by those providers. The CHWs are able to identify meds that are duplicate or expired. That helps us clinicians complete a proper medication reconciliation, which is also shared with their specialists. That type of medication reconciliation can eliminate a lot of issues for patients themselves."

With his decade of involvement with this model in today's fast-paced, high-tech medical environment, Cline commented that he really appreciates how this model elevates the fact that it's the simple things CHWs provide that make an exponential difference for patients. As exemplified by the Idaho model, that difference is often just building trust.

"Of course, patients want clinical competence," he said. "But what they really want from us is proof that we actually care. It's simple acts by CHWs that create a level of trust. That trust then allows us clinicians to make inroads because patients begin to share things they typically keep to themselves. In return, I can tell patients that I'm not here just to make their A1C better, I'm here to help improve their quality of life."